The Central Reframe

Most public discourse about AI and robotics treats automation as a labor market story. Will there be enough jobs? How do we retrain workers? What happens to inequality? Even the Universal Basic Income conversation tends to stay within this frame. It focuses on income replacement, poverty prevention, and maintaining consumer demand.

My Labor Zero thesis cuts deeper. It asks a different question entirely. What happens to bargaining power when human labor becomes optional?

You can solve the income problem by giving everyone money and still have a catastrophic power problem if the people receiving that money have no leverage over the people providing it. They become dependents, not citizens in any meaningful political sense. The provision can be withdrawn at any time because there is no structural mechanism to prevent withdrawal.

This reframe is the core of everything I have been working on. It is what makes the argument more than just another “robots are coming for your job” piece. The jobs question is downstream of the power question. We are looking at the wrong variable.

Think about what UBI looks like without leverage. Some authority decides you get money. That same authority can decide you do not. What recourse do you have? In a world where your labor is not needed, where your consumption is not necessary for the economy to function, where your compliance is enforced by automated systems rather than requiring your buy-in, the answer may be none. You have no recourse. You have no veto. You have no seat at the table.

This is not a story about poverty. Poverty can be solved with transfers. This is a story about power. And power is much harder to solve.

The Historical Mechanism: Why Labor Created Leverage

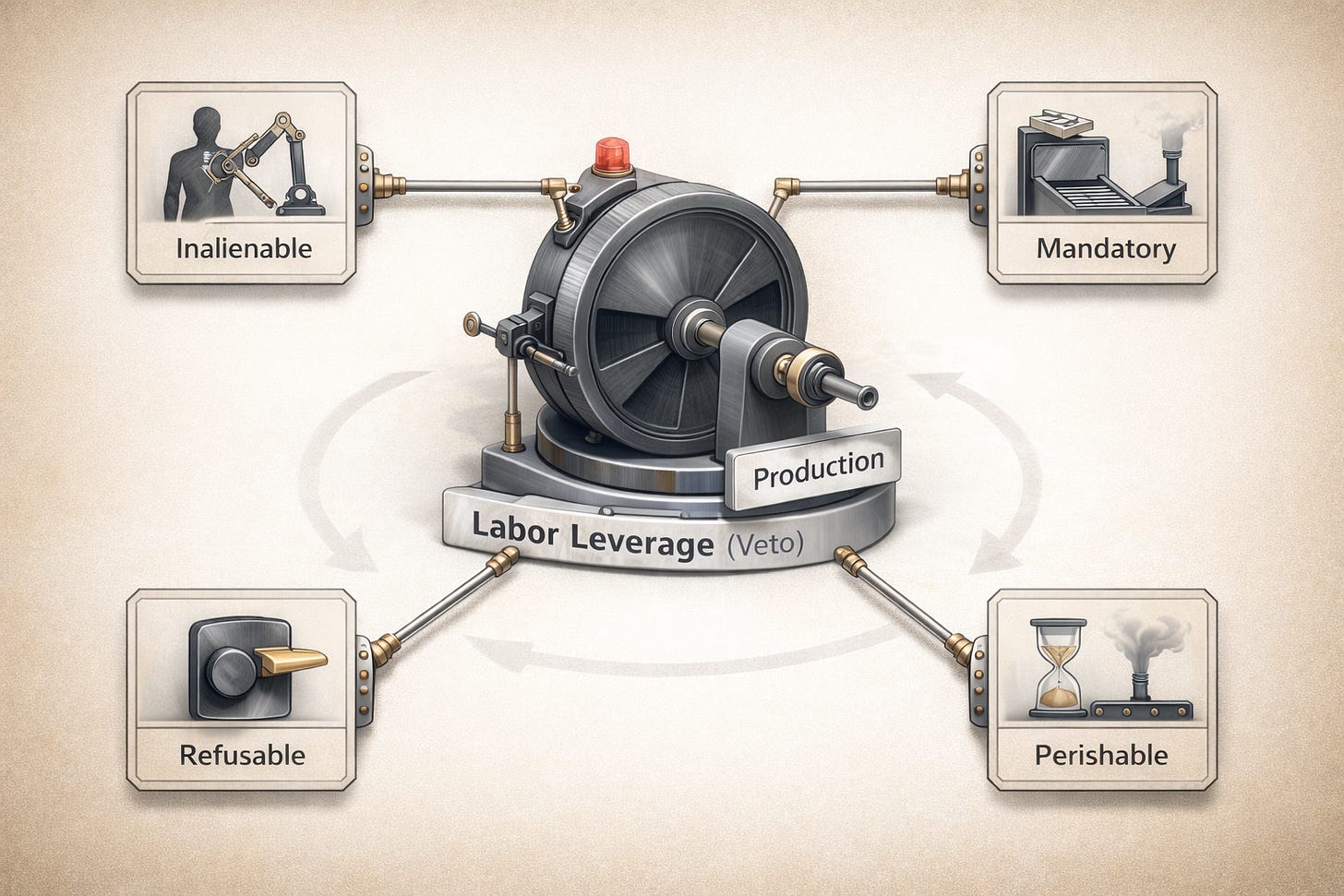

I have developed a framework around four properties of labor that made it a source of political leverage throughout the industrial era. Labor was inalienable, refusable, mandatory, and perishable. These are not just clever categories. They describe the structural features that created genuine interdependence between workers and the people who needed their work.

Labor was inalienable because you could not separate the work from the worker. You needed a physical, cooperative human body present. You could not extract the labor and leave the person behind. This meant that anyone who wanted work done had to negotiate with the people who could do it.

Labor was refusable because workers could always say no. They could strike. They could desert. They could seize the factory. This was the core of credible threats. The ability to shut down production created a veto point that forced negotiation.

Labor was mandatory because elites required it to generate wealth or wage war. There was no alternative. If you wanted things built, you needed workers to build them. If you wanted wars fought, you needed soldiers to fight them.

Labor was perishable because it could not be stored. Every day a worker strikes is value lost forever. Production lost today cannot be recovered tomorrow. This created urgency. It put immediate pressure on anyone whose operations depended on continuous labor.

Together these properties created structural interdependence. Elites needed labor not because they liked workers but because production required bodies. That need created a veto point. Workers could halt production. The costs of that halt were immediate and real because labor is perishable. Those costs could not be avoided by dealing with someone else because labor is inalienable and you needed those specific workers, not abstract labor power.

But there is something even more fundamental here that deserves emphasis. The implicit violence backstop.

This is uncomfortable territory. But I think intellectual honesty requires naming it. The welfare state, labor rights, social democracy. These emerged not just because strikes were costly, but because elites believed the alternative to concessions might be revolution. The Paris Commune. The Russian Revolution. The Spartacist uprising. The labor radicalism of the 1930s. These were not abstract threats. They were live possibilities that concentrated elite minds wonderfully.

When labor organizers in the early 20th century sat across the table from industrialists, there was an unspoken presence in the room. The specter of what happened to ruling classes that pushed too hard. Concessions were cheaper than confiscation or worse.

This matters for the Labor Zero thesis because it reveals that even labor leverage had a backstop. And that backstop may itself be eroding. Automated surveillance, predictive policing, autonomous security systems, algorithmic crowd control. All of these shift the balance between mass mobilization and elite enforcement. If a relatively small number of humans operating automated systems can suppress mass unrest, then even the ultimate leverage point becomes less credible.

We are not just losing labor leverage. We may be losing the backup leverage that made labor leverage effective.

The Outside Option as Threat Infrastructure

Here is one of the most important reframes in the entire Labor Zero project. A basic income floor is not charity. It is threat infrastructure.

The game-theoretic logic is straightforward. A credible threat requires that the threatening party can survive the conflict. If workers are paycheck-to-paycheck, they cannot sustain a strike. If consumers are desperate, they cannot maintain a boycott. If citizens are facing eviction, they cannot hold out for better terms.

This means that any post-labor leverage mechanism requires what we might call slack or slack capacity among the population. People need to be able to absorb short-term costs in order to impose long-term costs on targets.

UBI in this framing is not a humanitarian afterthought or a consolation prize for the displaced. It is a precondition for the viability of any alternative leverage mechanism. Without it, boycotts collapse, coordination fails, and collective action problems become insurmountable.

This reframe might resonate with people who are skeptical of UBI as giving away money for nothing. It is not that. It is creating the material conditions under which citizens can credibly threaten to impose costs on powerful actors. It is the foundation of a functioning power equilibrium, not a departure from one.

Consider the mechanics. You want to organize a consumer boycott against a company that is behaving badly. For that boycott to work, participants need to be able to forgo purchases for an extended period. They need to be able to accept inconvenience. They need to have alternatives. If people are living on the edge, if missing a paycheck means missing rent, if every purchase decision is constrained by desperation, then the boycott cannot hold. People defect because they have to.

The same logic applies to any form of collective action. Strikes work when workers have savings or strike funds to sustain them. Political movements work when participants have the time and resources to organize. Exit works as a threat only when the party threatening exit can actually survive leaving.

A universal basic income or some equivalent form of guaranteed material security is not about making people comfortable. It is about making credible threats possible. It is the infrastructure on which all other leverage mechanisms depend.

The Idealist vs. Realist Tension

This is where debates about Labor Zero often get stuck. I want to unpack the tension between what I call the idealist and realist positions, because understanding this distinction clarifies what we are actually trying to accomplish.

The idealist position says that political order rests on legitimating narratives. People comply because they believe the arrangement is just, or at least acceptable. Change the story. Develop better philosophical arguments. Shift cultural norms. Appeal to shared values. And you change what arrangements are possible.

The realist position says that political order rests on power equilibria. People comply because defection is costly. Arrangements persist because no actor can profitably change them. Legitimating narratives are either effects of power distributions or tools for reducing enforcement costs, not independent causes.

My observation is that the idealist position has a hidden assumption. It assumes elites care what non-elites think. And that caring is itself a function of interdependence. Elites care about legitimacy because delegitimation is costly. It raises enforcement costs. It invites coordination against them. It creates reputational risk. And in the limit, it triggers the violence backstop.

But if elites do not need non-elites for anything, then why would they care about legitimating narratives? Not labor. Not military service. Not consumption if we imagine AI-based economies that do not depend on mass consumer demand. Not even the passive compliance that makes rule cheap. If none of these dependencies exist, the motivation to care about legitimacy evaporates.

The idealist path assumes continued leverage. It assumes that persuasion can work because elites have some reason to listen. The Labor Zero scenario specifically negates that assumption.

That said, there is a useful reconciliation that I want to preserve. Legitimacy is a force multiplier. Leverage is the base load. You need both. But in the limit case, when interests diverge sharply and power is asymmetric, only leverage constrains.

This formulation allows us to acknowledge the idealist concerns. Yes, legitimating narratives matter for reducing enforcement costs and recruiting coalitions. But they only matter given a substrate of structural leverage. Without that substrate, narratives are just stories we tell ourselves while power operates unchecked.

Think about what this means practically. If you are trying to build a better future in the face of automation, the idealist approach says you should develop compelling philosophical arguments for why everyone deserves dignity and security regardless of economic contribution. Persuade people. Shift the narrative. Eventually the new story becomes the legitimating framework for post-labor institutions.

The realist approach says that is not enough. Political arrangements reflect underlying power balances. The welfare state and labor rights emerged because labor had leverage. Elites made concessions because the cost of concessions was lower than the cost of conflict. If labor leverage disappears, the structural basis for those concessions disappears. No amount of philosophical argument will maintain arrangements that are no longer in the interest of those with power to maintain.

The task is not primarily about persuasion. It is about building new structural leverage in forms appropriate to new conditions. The legitimating stories will follow. Or they will be irrelevant.

Alternative Leverage Mechanisms: An Honest Assessment

If labor leverage is eroding, what might replace it? I have surveyed various candidates and want to offer an honest assessment of where they stand.

Consumer boycotts and consumption strikes represent the most obvious substitute. If we cannot strike as workers, perhaps we can strike as consumers. The Target boycott provides an instructive example of how decentralized coordination can impose real costs on a corporation, affecting leadership and policy.

But boycotts have significant limitations. They require substitutes. You can only boycott Target if you can shop at Costco. They are episodic rather than continuous. Sustaining a boycott over time is difficult as attention wanes and fatigue sets in. They affect consumer-facing companies more than B2B or capital-goods producers. And they can be captured or fragmented by counter-campaigns. Boycotts are promising but not a general solution.

Radical transparency following models like Ukraine’s Prozorro procurement system represents another avenue. The concept is that everyone sees everything. Complete transparency in government spending prevents corruption and shifts discretionary power from elites to citizens.

But transparency is powerful yet insufficient alone. Prozorro works because transparency is coupled to enforcement mechanisms. Procurement exclusion, audit trails, legal consequences. Transparency without teeth is open-data theater. The challenge is that creating and maintaining enforcement mechanisms is itself a power question. You need leverage to establish the institutions that would provide transparency, and transparency alone does not create leverage.

Digital democracy tools like vTaiwan and Polis are fascinating for consensus-finding. They use algorithms to cluster viewpoints and surface agreement rather than generating division. But they face the same problem. Voice without binding consequences is cheap talk. These tools only matter if they are coupled to actual decision authority. If the outputs trigger rule-bound policy consequences rather than merely informing discretionary leaders. Otherwise they are participation theater.

Blockchain and self-sovereign identity are often oversold as solutions. The technology is less important than the governance question. Append-only logs are useful for tamper-evidence. But they do not solve who sets the rules, who enforces them, or what happens when powerful actors want to change them. Estonia’s e-governance works not because of blockchain per se, but because of broader institutional commitments that the technology supports.

Data leverage represents a theoretically interesting but practically limited option. If AI systems depend on ongoing data from users, perhaps coordinated data withholding could impose costs. But foundation models may not need ongoing data once trained. Individual data contributions may be too low-value to create meaningful bargaining power. Collective data rights could matter, but require legal frameworks that themselves require leverage to achieve.

Ownership redistribution is probably the most promising structural solution. If everyone owns a piece of the productive apparatus through sovereign wealth funds with citizen dividends, universal capital grants, or expanded stock ownership, then everyone has leverage as an owner, not just as a worker.

But ownership redistribution has a chicken-and-egg problem. You need leverage to achieve ownership redistribution, but ownership redistribution is supposed to be the source of new leverage. This argues for using remaining labor leverage to push for ownership redistribution now, before that leverage evaporates. The window is open but closing.

Legal and regulatory leverage is underappreciated. Private rights of action, class aggregation mechanisms, whistleblower bounties, fiduciary duties. These create enforcement channels that do not depend on captured regulators. They convert diffuse harm into concentrated legal pressure. This might be one of the more robust post-labor levers because it operates through institutions that already exist and have established legitimacy.

Energy and infrastructure constraints offer a different kind of leverage because they are rooted in physical reality rather than purely informational or financial flows. Artificial intelligence systems require enormous amounts of electricity. Data centers consume power on an industrial scale, and that power must come from somewhere. The land on which these facilities sit requires permits. The electricity they draw requires grid connections and regulatory approval. Local governments retain authority over zoning decisions, environmental review processes, and utility rate structures. These institutional controls create points of friction that cannot easily be circumvented through automation or capital mobility alone. However, maintaining these controls requires that democratic institutions retain actual authority over the decisions that matter, and this brings us back to the central problem. If the institutions that might provide leverage are themselves captured or hollowed out, then the physical constraints offer little practical protection.

The Time Dimension

One of the most important strategic insights in the Labor Zero framework is temporal. There is a window.

Human labor still retains economic value in many sectors. Labor movements, while weakened, still exist. Democratic institutions, while stressed, still function. The leverage has not fully evaporated yet.

The strategic implication is that this window should be used to establish institutional arrangements that will persist after labor leverage disappears. Use remaining leverage now to push for ownership redistribution through sovereign wealth funds, universal capital grants, and expanded employee ownership. Embed rights constitutionally including the right to basic income and the right to cognitive liberty. Build coordination infrastructure through cooperative platforms, federated services, and alternative payment rails. Test and scale new coordination mechanisms like quadratic voting and participatory budgeting at meaningful scale.

This is exactly analogous to how early 20th century labor movements used their leverage to establish institutions that persisted and provided ongoing protection. Unions. Labor law. Social insurance. These were not gifts from benevolent elites. They were extracted through the credible threat of labor withdrawal, amplified by the background threat of more radical action. The institutions persisted even as the immediate leverage that created them waned.

The question is whether we can do something similar before the current window closes. Whether we can use the leverage we still have to lock in arrangements that will protect people after that leverage is gone.

The timeline is uncertain but probably measured in years to a few decades rather than generations. The trajectory of AI capabilities, the pace of robotics development, the diffusion of automation across sectors. All of these are accelerating. Every year we delay is a year in which remaining leverage erodes.

The Historical Default Problem

Here is a thought that I find genuinely disturbing. And I think it needs to be central to how we understand what is at stake.

The useless class scenario is not dystopian fiction. It is the historical default.

Most premodern societies contained large populations who possessed no political leverage whatsoever. Peasants worked land they did not own and could not leave. Serfs were bound to estates by law and custom. Slaves existed as property. Conquered peoples lived under the authority of foreign rulers who owed them nothing. All of these groups survived at the sufferance of elites, with no structural mechanism for improving their condition or holding power accountable. Mobility between classes approached zero, and this arrangement persisted not for decades but for centuries.

The period roughly 1850 to 2050 during which labor scarcity gave ordinary people bargaining power might be the anomaly, not the norm. Industrialization created dependence on mass labor. That dependence created leverage. That leverage produced the welfare state, labor rights, democratic participation, and rising living standards.

If automation removes the dependence, we may be reverting to the historical mean.

This framing is useful because it raises the stakes without seeming alarmist. We are not predicting some unprecedented dystopia. We are observing that the conditions which produced the relatively egalitarian arrangements of the 20th century were historically unusual, and those conditions may be ending.

For most of human history, the majority of people had no structural leverage over the minority who controlled resources and violence. The moral arguments against this arrangement were always available. Philosophers and prophets in every era articulated versions of human dignity and equality. But those arguments did not produce change on their own. What produced change was the industrial revolution creating a situation where elites genuinely needed mass labor.

That situation gave ordinary people something elites wanted. And because they had something elites wanted, they could bargain. They could strike. They could threaten. They could extract concessions. Not because elites were good or became convinced by moral arguments. But because the structure of production gave workers a veto.

If that veto is removed, we should expect reversion to the historical pattern. Not because anyone is particularly evil. But because the structural constraint that made egalitarian arrangements rational for elites will no longer exist.

This is what I mean when I say Labor Zero is my most dangerous idea. It is not dangerous because it advocates for anything harmful. It is dangerous because it names clearly a threat that most people have not fully grasped. The era of labor leverage may be ending. And if we do not build replacement leverage before it ends, we may find ourselves in a world where the majority of humanity has no structural power over its own conditions.

That is the future we have to prevent. And preventing it requires understanding that the enemy is not villainy but structural dynamics. It requires understanding that the solution is not better arguments but better leverage. It requires acting now, while we still can, to build the institutions and mechanisms that will matter when labor no longer does.

The clock is running. The window is open. But it will not stay open forever.

Notes

The Central Reframe

Sam Altman, remarks at OpenAI Dev Day, October 6, 2025, as reported in Maxwell Zeff, “Sam Altman Says ChatGPT Has Hit 800M Weekly Active Users,” TechCrunch, October 6, 2025, https://techcrunch.com/2025/10/06/sam-altman-says-chatgpt-has-hit-800m-weekly-active-users/. The figure of roughly one-tenth of the global population using AI weekly provides the empirical anchor for the scale of transformation. This is not a niche technology. It is the fastest adoption of any consumer product in history, surpassing even the initial growth curves of social media platforms.

OpenAI, “The State of Enterprise AI: 2025 Report,” OpenAI, 2025, https://openai.com/index/the-state-of-enterprise-ai-2025-report/. This report documents not just user growth but intensifying usage. Message volume has grown faster than user volume, meaning people are not just signing up but increasingly integrating AI into daily workflows. Seventy-five percent of workers report AI has improved either speed or quality of output, with average time savings of 40 to 60 minutes per day.

The Historical Mechanism: Why Labor Created Leverage

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 1944; second edition, 2001). Polanyi’s concept of labor as a “fictitious commodity” provides the theoretical foundation for understanding why labor cannot be treated like ordinary market goods. Labor is inseparable from the human beings who provide it, cannot be stored, and must be protected from pure market logic lest the social fabric disintegrate. His analysis remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the political economy of work.

Joy Paton, “Labour as a (Fictitious) Commodity: Polanyi and the Capitalist ‘Market Economy,’” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 21, no. 1 (October 2010): 77-88, https://doi.org/10.1177/103530461002100107. This article extends Polanyi’s analysis to contemporary conditions, arguing that the tension between treating labor as a commodity and protecting its human dimensions remains the central contradiction of market economies. Paton emphasizes that labor’s “fictitious” status means it necessarily requires institutional protection.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members Summary—2024,” news release, January 28, 2025, USDL-25-0105, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm. The union membership rate fell to 9.9 percent in 2024, a record low. In 1983, the first year for which comparable data are available, the rate was 20.1 percent. Private sector unionization has fallen to just 5.9 percent. These figures document the erosion of labor’s traditional institutional infrastructure.

U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Labor Unions and the U.S. Economy,” October 26, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/labor-unions-and-the-us-economy. This Treasury Department analysis confirms that union membership peaked in the 1950s at approximately one-third of the workforce, coinciding with the lowest levels of income inequality since the Great Depression. The subsequent divergence between declining union density and rising inequality is documented extensively.

Congressional Research Service, “A Brief Examination of Union Membership Data,” Report R47596, Library of Congress, 2023, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47596. Union density peaked at 33.5 percent in 1954, representing a 23.4 percentage point decline to 2022 levels. While union election petitions have increased in recent years, overall membership continues its structural decline.

Jake Rosenfeld, “The Rise and Fall of US Labor Unions, and Why They Still Matter,” The Conversation, June 30, 2025, https://theconversation.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-us-labor-unions-and-why-they-still-matter-38263. This analysis documents how unions’ equalizing impact extended beyond their own members. Research found that nonunion workers in strongly unionized industries and areas enjoyed substantially higher pay through spillover effects, demonstrating that the benefits of labor power were broadly distributed.

The Outside Option as Threat Infrastructure

Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970). Hirschman’s framework distinguishes between “exit” and “voice” as mechanisms for expressing dissatisfaction and forcing organizational change. The Labor Zero problem can be understood as the erosion of labor’s traditional “voice” mechanism, requiring new forms of leverage that may emphasize different combinations of exit and voice.

Economic Policy Institute, “16 Million Workers Were Unionized in 2024: Millions More Want to Join Unions but Couldn’t,” February 2025, https://www.epi.org/publication/millions-of-workers-millions-of-workers-want-to-join-unions-but-couldnt/. The disconnect between growing interest in unionization and declining unionization rates reflects aggressive employer opposition combined with labor law that fails to protect workers’ right to organize. Research shows that 60 million workers would join a union if they could. This gap between desire and capability illustrates the structural barriers to traditional leverage.

The Idealist vs. Realist Tension

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London: Andrew Crooke, 1651). The social contract tradition begins with Hobbes’s argument that political authority derives from rational consent under conditions of hypothetical state of nature. However, Hobbes himself was deeply realist, recognizing that the sovereign maintains order through power rather than mere legitimacy. The “bait-and-switch” between legitimating narrative and material enforcement runs through the entire social contract tradition.

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Talcott Parsons (New York: Scribner’s, 1930; originally published 1905). Weber’s analysis of how Calvinist doctrine created a psychological framework that encouraged industriousness while forbidding wasteful consumption remains foundational for understanding the moralization of work in Western societies. The persistence of work ethic ideology after secularization creates the existential vacuum that Labor Zero exposes.

Alternative Leverage Mechanisms: An Honest Assessment

Steven Kelman, “Overcoming Corruption and War: Lessons from Ukraine’s ProZorro Procurement System,” Harvard Kennedy School, Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, 2023, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/overcoming-corruption-and-war-lessons-ukraines-prozorro-procurement-system. ProZorro has helped Ukraine save almost $6 billion in public funds since October 2017, according to the December 2021 U.S. Strategy on Countering Corruption. The system demonstrates how radical transparency can create accountability mechanisms that reduce corruption, though it works only because transparency is coupled to enforcement through procurement exclusion and audit trails.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, “The Impact of the Prozorro Procurement System on the Ukrainian Economy,” Law in Transition Journal 2025, https://www.ebrd.com/content/dam/ebrd_dxp/assets/pdfs/legal-transition/Law%20in%20Transition%20journal/LiTJ%202025/ebrd-lit25-the-impact-of-the-prozorro-procurement-system-on-the-ukrainian-economy.pdf. Updated figures suggest Prozorro has saved more than $8.7 billion since its launch, while the number of domestic commercial firms bidding for public contracts has risen from 14,000 in 2014 to 140,000 in 2024.

Open Contracting Partnership, “Ukraine’s Open Contracting Impact,” March 2024, https://www.open-contracting.org/impact-stories/impact-ukraine/. After the Maidan revolution, reformers created a radically transparent e-procurement system enabling government agencies to conduct procurement fully transparently. The system was built on principles of impartial decision-making and transparency as keys to post-Soviet reform. It persisted through the Russian invasion, demonstrating institutional resilience.

vTaiwan, official website, https://info.vtaiwan.tw/. vTaiwan utilizes Pol.is, a digital platform for opinion collection, to facilitate large-scale conversations and consensus building. The tool has been pivotal in achieving “rough consensus” on various policy issues at the national level, addressing scalability challenges in deliberative democracy. Since 2015, over 80 percent of vTaiwan deliberations have led to decisive government action.

The Computational Democracy Project, “vTaiwan Case Study,” https://compdemocracy.org/case-studies/2014-vtaiwan/. vTaiwan is an open consultation process that brings citizens and government together to deliberate and reach rough consensus on national issues. Taiwan has generated more case studies on using Polis in the process of creating national legislation than any other country. The Uber regulation case demonstrated how the platform could break legislative deadlock by surfacing hidden consensus.

Participedia, “vTaiwan Method,” https://participedia.net/method/vtaiwan. The government has executed over 80 percent of vTaiwan’s proposals. While the process has not been particularly broad reaching, it leads to deep consultation and higher likelihood of action. Analysts, participants, and local media have praised the initiative as a successful way to form consensus between citizens and government.

Colin Megill, Christopher Small, and Michael Bjorkegren, Pol.is project, as described in “Pol.is,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pol.is. Pol.is was founded after the Occupy Wall Street and Arab Spring movements. It has been used in Taiwan, America, Canada, Singapore, Philippines, Finland, Spain and other governments. Anthropic used Polis to draft a publicly sourced constitution for an AI system, demonstrating applications beyond traditional governance.

Steven P. Lalley and E. Glen Weyl, “Quadratic Voting: How Mechanism Design Can Radicalize Democracy,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 108 (May 2018): 33-37, https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181002. Quadratic voting allows individuals to pay for as many votes as they wish using “voice credits,” where the cost increases quadratically. This mechanism promises to correct the failure of existing democracies to incorporate intensity of preference and knowledge. The formal proof demonstrates efficiency properties under specific conditions.

RadicalxChange Foundation, “Quadratic Voting,” https://www.radicalxchange.org/wiki/quadratic-voting/. Quadratic Voting greatly mitigates tyranny-of-the-majority and factional control problems. The mechanism has been deployed in Colorado legislative priority-setting, Taiwan’s Presidential Hackathon, and various blockchain governance applications. Implementation challenges include sybil resistance and preventing wealth capture.

Vitalik Buterin, Zoë Hitzig, and E. Glen Weyl, “A Flexible Design for Funding Public Goods,” Management Science 65, no. 11 (2019): 5171-5187. Quadratic funding extends the quadratic voting principle to resource allocation, dramatically amplifying the impact of many small contributors relative to few large ones. The mechanism allows for optimal production of public goods without centralized legislature determination.

The Target Boycott Case Study

Nathaniel Meyersohn, “Target’s CEO Is Stepping Down as Customers Turn Away,” CNN Business, August 20, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/08/20/business/target-stock-ceo-cornell. Target CEO Brian Cornell stepped down after 11 years, amid slumping sales and backlash to the company’s retreat on DEI policies. The decision to end some DEI programs angered supporters who felt blindsided by Target, given the company’s previous deep investment in diversity initiatives.

Slate, “Target: The Anti-Trump Resistance Just Got Its Bud Light Moment,” August 21, 2025, https://slate.com/business/2025/08/target-ceo-brian-cornell-dei-boycott-trump-maga.html. Target’s stock value plummeted 64 percent from pandemic-era highs. During the May earnings call, Cornell explicitly acknowledged “the reaction to the updates we shared on DEI in January” as one of “several headwinds” facing the company. The boycott, led by Pastor Jamal Bryant since February, demonstrated how decentralized consumer coordination could impose material costs on corporate decision-making.

Blavity, “Target CEO Stepping Down as DEI Rollback Backlash Continues and Profits Drop,” August 20, 2025, https://blavity.com/target-ceo-stepping-down-amid-dei-rollback-backlash. Foot traffic to Target stores steadily declined for months as the boycott continued. The case illustrates both the potential and the limitations of consumer action as a leverage mechanism. The boycott succeeded in imposing costs but faced challenges in achieving full policy reversal, with activists noting that “leadership change doesn’t mean anything without a culture change.”

The Time Dimension

World Economic Forum, “Yuval Harari’s Blistering Warning to Davos,” January 2020, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2020/01/yuval-hararis-warning-davos-speech-future-predications/. Harari warned that automation will soon eliminate millions of jobs, and people will have to reinvent themselves repeatedly throughout their lives. Those who fail in the struggle against irrelevance would constitute a new “useless class,” people useless not from the viewpoint of friends and family but from the viewpoint of the economic and political system.

Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (New York: Harper, 2017), excerpt published as “The Rise of the Useless Class,” TED Ideas, July 25, 2024, https://ideas.ted.com/the-rise-of-the-useless-class/. Harari argues that in the twenty-first century we might witness the creation of a massive new unworking class: people devoid of any economic, political, or even artistic value. This “useless class” will not merely be unemployed but unemployable. The concept crystallizes the political stakes of automation beyond mere job displacement.

Psychology Today, “Surviving Within Artificial Intelligence’s Useless Class,” February 11, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/word-less/202502/surviving-within-artificial-intelligences-useless-class. Beyond economic considerations, the article addresses the psychological and existential dimensions of potential mass irrelevance. Involuntary unemployment has profound effects on mental health, and the “useless class” scenario raises questions about meaning and purpose that technocratic solutions like UBI cannot fully address.

The Historical Default Problem

NBER Working Paper No. 23516, “Unions, Workers, and Wages at the Peak of the American Labor Movement,” https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23516/w23516.pdf. This analysis of the high point of American unionization documents how unions reduced wage inequality in the 1950s. Selection into unions was negative in that union workers had lower education levels and fathers with lower occupational status than non-union workers, yet they earned premiums. The counterfactual in which union members are paid like non-union members suggests that unions substantially compressed the overall wage distribution.

Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee, “A Brief History of the Growth of Unions,” October 28, 2025, https://workerorganizing.org/premajority-unionism/unions/history/. The labor movement grew dramatically in the 1930s through the 1940s and reached a peak of over one-third of the U.S. workforce in the 1950s. By then, unions had become established institutions. The reasons for subsequent decline have been greatly debated for decades and constitute one of the most serious problems facing the labor movement.

NPR Planet Money, “50 Years of Shrinking Union Membership, in One Map,” February 23, 2015, https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2015/02/23/385843576/50-years-of-shrinking-union-membership-in-one-map. Fifty years ago, nearly a third of U.S. workers belonged to a union. Today, it is one in ten. The Midwest, once full of manufacturing jobs and the highest concentration of union workers in America, has seen dramatic change as manufacturing jobs fell and fewer remaining manufacturing jobs are held by union workers. The public sector now represents the remaining concentration of union power.

ScienceDirect, “Union Organizing Effort and Success in the U.S., 1948-2004,” December 17, 2008, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0276562408000346. In 1950, historian Arthur Schlesinger assessed the “upsurge of labor” as third in importance among events shaping the first half of the twentieth century, behind only the two world wars. By contrast, the last half-century has seen perhaps no social trend impacting the U.S. labor force with more far-reaching effects than the decline of union membership. The paper documents the long-term decline in both union organizing effort and success.

Note on methodology: These notes were compiled through web research conducted in January 2026, verifying claims made in the text against primary sources and authoritative secondary sources. Annotations provide context for why each source matters to the argument and what specific evidence it contributes. All URLs were accessible at the time of research.