The investment case for OpenAI has never been more precarious than it is right now in late 2025. What was once a company that seemed destined to dominate the artificial intelligence revolution has revealed itself to be a structurally disadvantaged challenger fighting a defensive war on multiple fronts. The company anticipates burning through roughly $9 billion this year on $13 billion in sales, a cash burn rate of approximately 70% of revenue. This is not the profile of a company poised to capture monopolistic profits from a transformative technology; it is the profile of a utility company spending astronomical sums to deliver a commodity product that competitors are increasingly giving away for free.

The financial trajectory only becomes more alarming when examined over a longer time horizon. The documents show OpenAI projects that by 2028, its operating losses will balloon to roughly three-quarters of that year’s revenue, driven primarily by ballooning spending on computing costs. The company has painted a rosy picture of eventual profitability by 2029 or 2030, but this projection requires believing that OpenAI can grow revenue from roughly $13 billion today to $125 billion or more while simultaneously maintaining pricing power in a market where every major technology company and numerous startups are racing to commoditize the very product OpenAI sells. The cash burn is expected to reach $115 billion cumulatively through 2029, according to The Information. These numbers represent a staggering bet that requires near-perfect execution across multiple dimensions over half a decade.

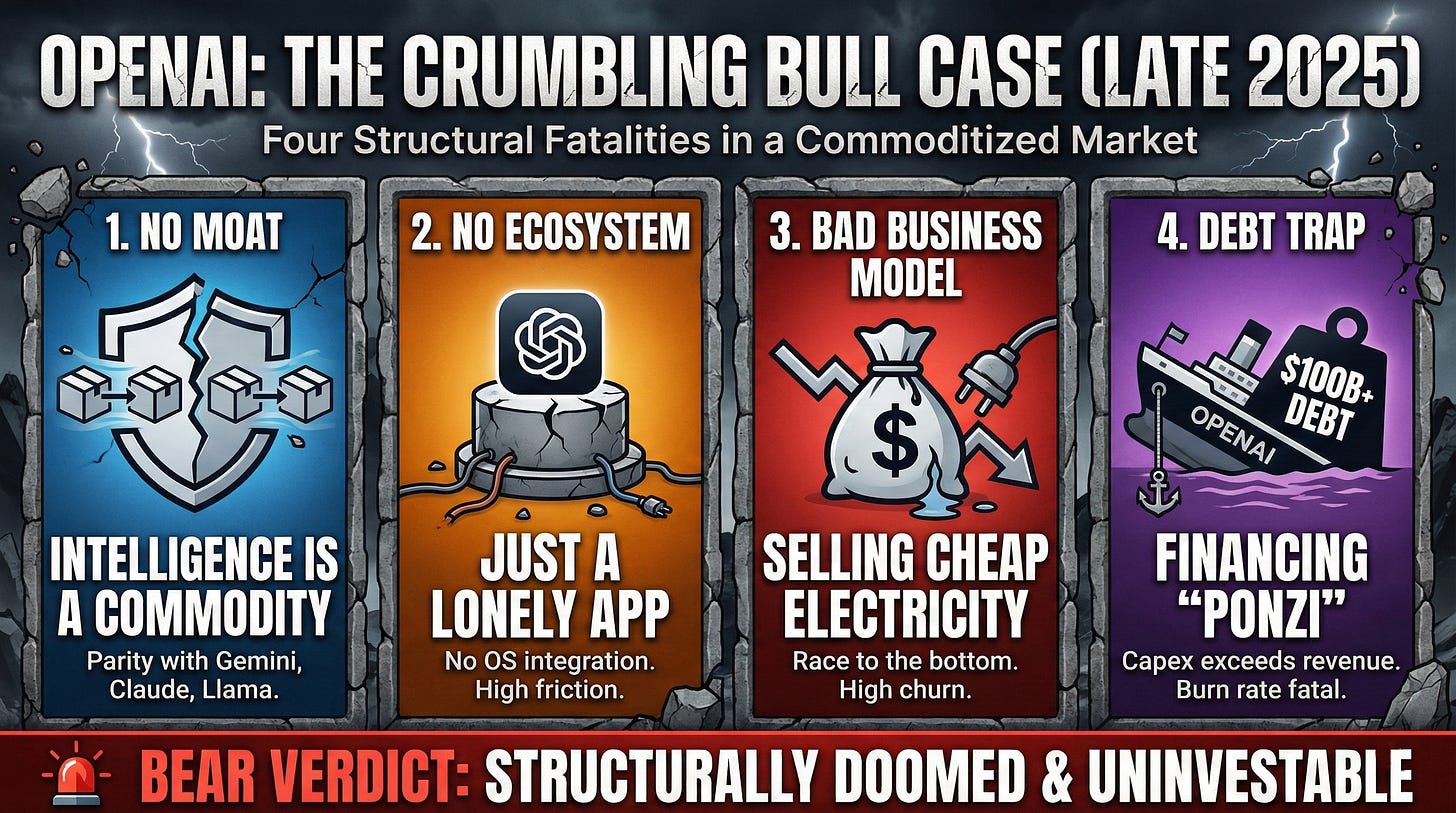

The most damning evidence against OpenAI’s long-term viability is the evaporation of its technological moat. In 2023, GPT-4 felt like genuine magic, a capability that no other company could replicate. Today, that lead has effectively vanished. The sudden availability of frontier-level open-source models is expected to dramatically accelerate AI development globally, potentially reshaping entire industries and altering the balance of power in the tech world. Meta’s Llama series, Mistral’s increasingly capable models, and even Chinese competitors like DeepSeek have demonstrated that the core technology powering ChatGPT is replicable and, in many cases, distributable for free. When your product becomes commoditized, the economics become brutal, and OpenAI finds itself in the position of trying to sell bottled water in a world where tap water has become indistinguishable in quality.

The competitive pressure from open-source alternatives is compounding rapidly. The open source movement in AI has grown exponentially over the past few years. Instead of relying solely on expensive, closed models from major tech companies, developers and researchers worldwide can now access, modify, and improve upon state-of-the-art LLMs. This democratization is existential for OpenAI’s business model. Enterprises that once paid premium prices for API access now have the option to run comparable models on their own infrastructure at a fraction of the cost, with the added benefits of data privacy and customization. The value proposition that justified OpenAI’s premium pricing has eroded faster than anyone anticipated, and there is no indication that this trend will reverse.

Perhaps nothing illustrates OpenAI’s structural weakness more clearly than the behavior of its most important partner. Microsoft is dancing to its own tune in the artificial intelligence revolution, and Wall Street cannot stop watching. Despite pouring approximately $13 billion into OpenAI over several years, DA Davidson analyst Gil Luria estimates that just 17 percent of Microsoft’s total Azure revenue comes from artificial intelligence workloads. More critically, only 6 percent of that total ties directly to reselling OpenAI’s models, while approximately 75 percent is generated from Azure AI. Microsoft is building its own models, hedging with Anthropic, and quietly reducing its dependency on the very company it funded. When your largest investor is simultaneously your biggest competitor and is actively developing alternatives to your core product, the strategic implications are dire.

Leaders at Microsoft believe Anthropic’s latest models — Claude Sonnet 4, specifically — perform better than OpenAI’s in certain functions, like creating aesthetically pleasing PowerPoint presentations. This is not a minor technical preference; it represents a fundamental shift in how Microsoft views its partnership with OpenAI. Microsoft is dramatically escalating its AI independence strategy. At an internal town hall Thursday, Microsoft AI chief Mustafa Suleyman revealed the company is making “significant investments” in compute capacity to build frontier models that can compete directly with OpenAI, Google, and Meta. The company that was supposed to be OpenAI’s path to distribution and scale is instead preparing for a future where OpenAI is just one vendor among many, if not an outright competitor.

The leadership exodus at OpenAI over the past year has been nothing short of catastrophic. In September 2024, Murati announced that she was stepping down as CTO. This move came amid a wider executive exodus as OpenAI chief research officer Bob McGrew and a vice president of research, Barret Zoph, also announced their departures soon after. Mira Murati was not a minor figure; she was instrumental in the development of ChatGPT, Dall-E, and Sora. Her departure, along with co-founder Ilya Sutskever, safety leader Jan Leike, and co-founder John Schulman who joined rival Anthropic, has left CEO Sam Altman without much of the leadership team that helped him build OpenAI into an AI juggernaut. Hannah Wong, the executive who steered OpenAI through its most chaotic period, has announced she’s leaving the company just this month, continuing the pattern of senior departures that suggests something fundamentally broken in the organization’s culture or direction.

The distribution problem facing OpenAI may be its most insurmountable challenge. Apple and Google control the smartphones that billions of people use every day. Microsoft controls the productivity software that enterprises depend upon. OpenAI, by contrast, must convince users to deliberately open a separate application and type their queries into a text box. In a world of agentic AI where assistants need access to your email, calendar, and files to be useful, an AI embedded directly into your operating system has an overwhelming structural advantage over a standalone chatbot. OpenAI is trying to be a consumer product company without owning any of the surfaces where consumers actually spend their time, competing against incumbents who can simply bundle AI capabilities directly into products that already have hundreds of millions of daily active users.

The nuclear-to-solar analogy captures the fundamental economic transformation that is devastating OpenAI’s business model. Just as nuclear power required enormous upfront capital expenditure for centralized power plants, AI in its current form requires massive data center investments to train and serve models. But the direction of travel is unmistakably toward distributed intelligence that runs locally on devices. A major part of the pitch is practicality. Lample emphasizes that Ministral 3 can run on a single GPU, making it deployable on affordable hardware — from on-premise servers to laptops, robots, and other edge devices that may have limited connectivity. When powerful AI models can run on a smartphone or a laptop without any cloud connection, the entire economic rationale for paying premium prices to access centralized AI infrastructure disappears. OpenAI is building nuclear reactors in a world that is rapidly installing solar panels on every rooftop.

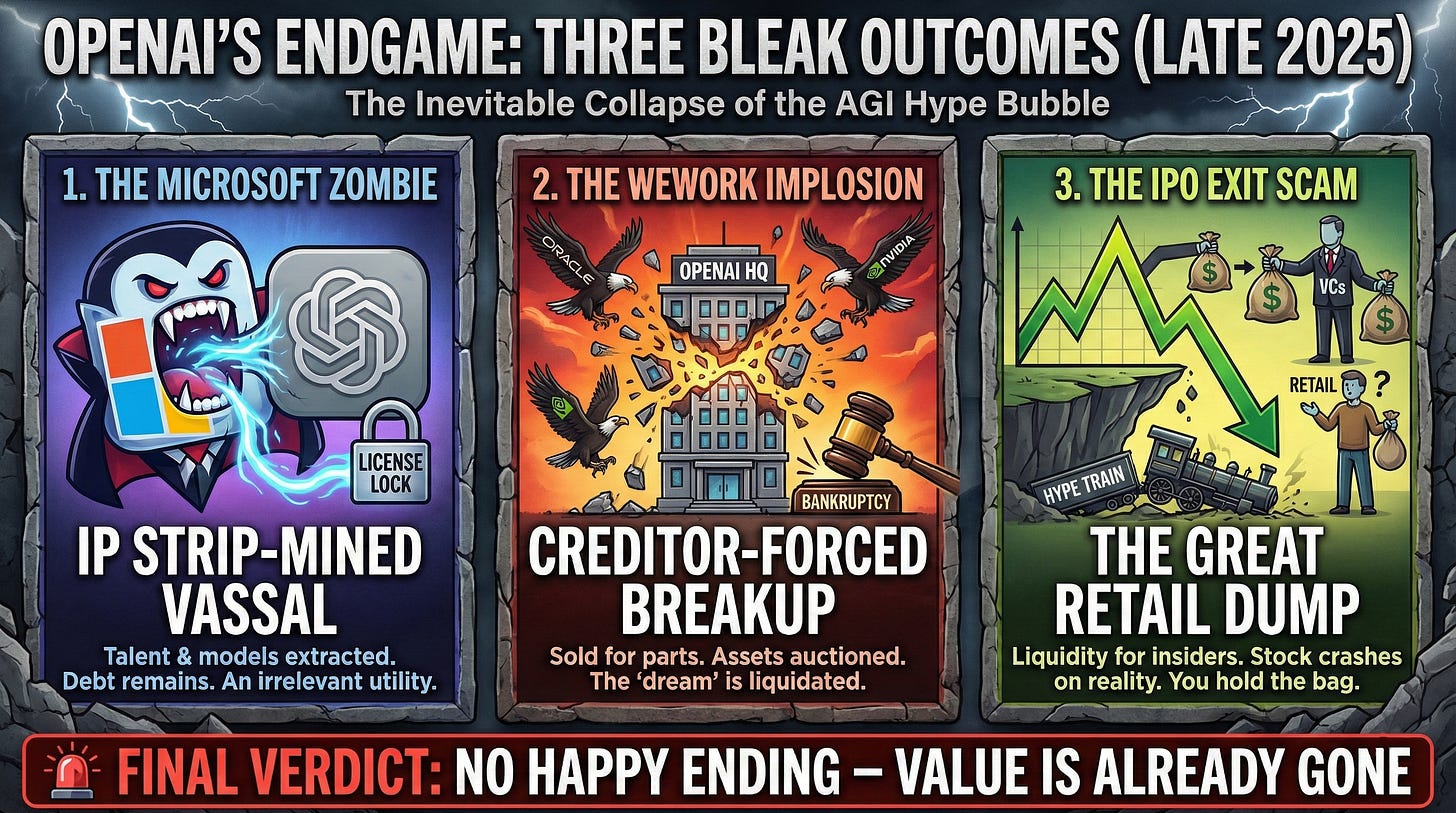

The proposed $1 trillion IPO valuation is perhaps the clearest signal that something is deeply wrong with the OpenAI story. In the first half of the year, OpenAI lost $13.5 billion, on revenue of $4.3 billion. It is on track to lose $27 billion for the year. One estimate shows OpenAI will burn $115 billion by 2029. Asking public market investors to pay $1 trillion for a company that loses more than twice as much as it earns is not a growth story; it is an exit strategy. The sophisticated investors who funded OpenAI’s private rounds are looking for a way to transfer their risk to retail investors and pension funds who may not fully understand the unit economics of the business. A recent report by HSBC estimated that the company will remain in the unprofitable category until 2029 and that the company will need an additional $207 billion to fund its ambitions.

Sam Altman’s leadership represents another structural liability for the company. His background is as a startup investor and evangelist, not as an operational executive who has scaled a capital-intensive industrial operation. The pivot from nonprofit research lab to for-profit corporation to public benefit corporation to anticipated public company has been accompanied by legal and governance structures designed primarily to protect Altman’s control rather than to create shareholder value. Going public means answering a lot more of those kinds of questions, every single quarter, forever. When asked about financial concerns in a friendly podcast interview, Altman’s dismissive response revealed a leader uncomfortable with the scrutiny that public markets will inevitably bring. The adults in the room have largely departed, leaving a company that desperately needs disciplined execution led by someone whose strengths lie elsewhere.

The comparison to Netscape is instructive. Netscape proved that the internet was real and created genuine value, but it had no sustainable moat against an incumbent who could bundle the browser directly into the operating system. OpenAI has proven that large language models are real and valuable, but it faces the same structural disadvantage against incumbents who can bundle AI directly into operating systems, productivity suites, and cloud platforms. The value will accrue to the companies that own the distribution channels and the hardware, not to the company that demonstrated the technology was possible. OpenAI is destined to become a historical footnote, remembered as the company that ignited the AI revolution but failed to capture the economic value it created.

The only bull case for OpenAI is the AGI lottery ticket: the possibility that the company achieves artificial general intelligence before anyone else and thereby transcends all normal economic analysis. But there is no evidence that OpenAI is any closer to AGI than Google, Anthropic, or DeepMind. The company’s advantage was never secret research breakthroughs; it was first-mover advantage in commercialization. That advantage has now been erased by competitors who can match or exceed OpenAI’s capabilities while benefiting from existing ecosystems, distribution channels, and the willingness to operate AI as a loss leader to drive engagement with more profitable products. The secret sauce was never secret, and there was never any sauce.

The endgame for OpenAI is unlikely to be the triumphant dominance that early investors imagined. The most probable outcomes range from gradual irrelevance as a backend provider, to financial restructuring under pressure from creditors, to absorption by Microsoft or another well-capitalized technology company looking to acquire the remaining talent and intellectual property at a discount. Despite its current losses, OpenAI’s long-term prospects are bolstered by the explosive growth of the AI market. But growth in the overall AI market does not guarantee success for any individual company, particularly one with no moat, no ecosystem, and a cost structure that requires selling a commodity at premium prices. The AI revolution is real, but OpenAI’s role in capturing its economic value is far from assured. For anyone considering an investment in OpenAI at anything close to current valuations, the prudent course is to stay far away and watch from the sidelines as economic reality catches up with hype.