Your degree is worthless (and losing value by the day)

Credential inflation started more than two centuries ago. AI is going to nuke the field. All fields. This is just the last act.

Bottom line up front: your degree is increasingly worthless today. But this is not a new trend.

Data shows that 40% of recent US graduates are underemployed.

Some of this can be explained by education/labor market mismatch—the running gag is “that women’s studies degree isn’t going to get you a job in STEM!” (or something to that effect).

During my tenure in corporate America, that was not necessarily true. The combination of OTJ training and any degree opened many doors. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the degree part, and I lost more than a few great job opportunities by companies (and federal bureaus) who required a college degree—any degree. It was explained to me that “a degree signifies your ability to trudge through BS work.”

This is the same reason that some companies like hiring military veterans—they don’t complain about grunt work and are used to being yelled at. I learned the hard way “Don’t apply to any company that touts ‘Vet Owned and Operated!’”

But I digress.

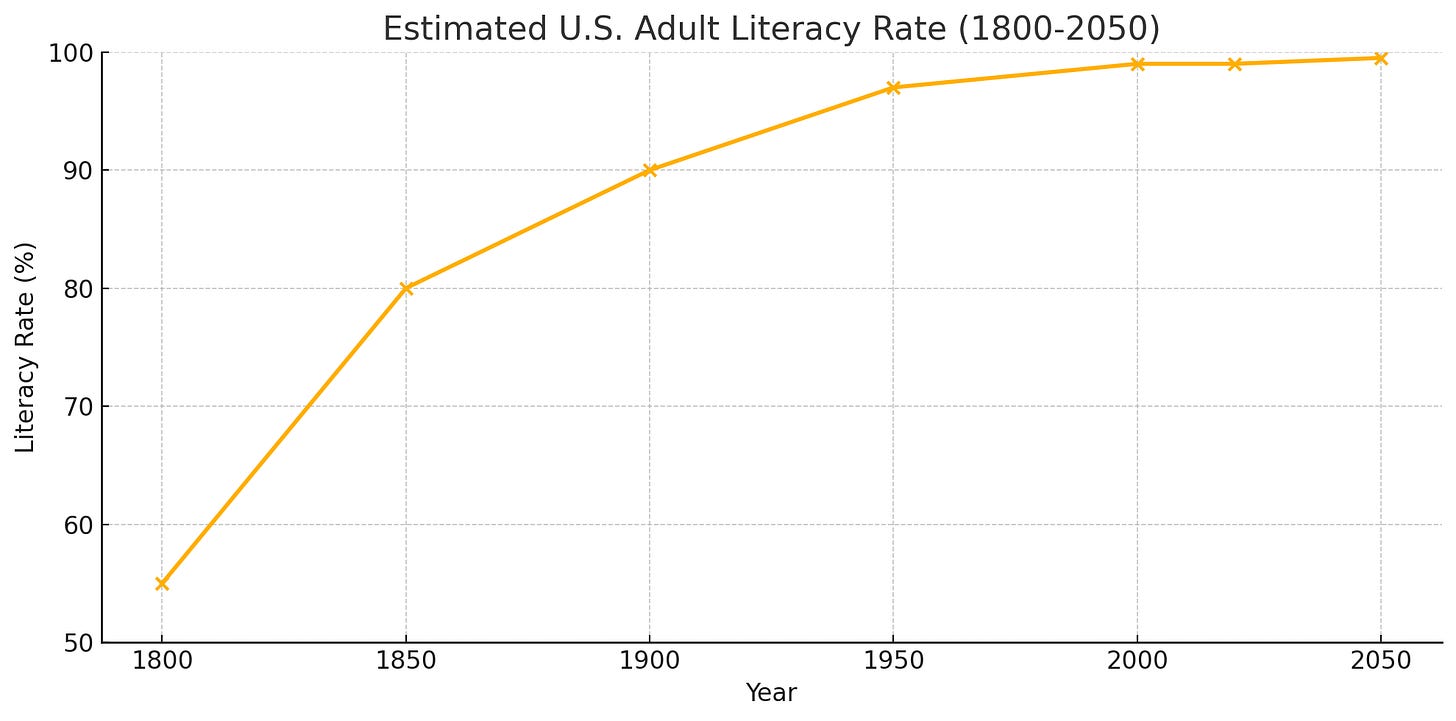

The above graphic came from an exploration of the last few decades of job dislocation and globalization. Certainly, millions of American jobs have gone overseas: manufacturing, customer support, and even high tech STEM jobs. There’s a good chance that the code running in your favorite apps was written in Thailand or Russia.

The fingerprints of domestic automation manifest in one simple way: productivity goes up (GDP per capita) while wages stagnate. The more automation a society has, the more productive it is overall, but the fewer jobs it needs.

But it occurred to me, the Industrial Revolutions have been displacing jobs for a while. And every time technology advances, so too do baseline literacy requirements.

Reading, writing, and arithmetic

When education first started becoming important, it was called the “Three R’s” for reading, writing, and reckoning (or arithmetic). Book literacy was the first kind of credential inflation. For centuries, humans got by with hands-on skills.

Then numeracy, then digital literacy. The minimum threshold of cognitive abilities has been rising steadily.

What happens when the median educational requirement in years is going up faster than the actual calendar is advancing? Within a few years, AI will be pushing the “baseline educational requirement” up by 2 years for every birthday you have. You’ll never catch up.

My assertion here is simple: Post-Labor Economics started a long time ago.

Marx and Keynes weren’t wrong, just early.

Marx predicted machinery would “render the worker superfluous”—he just misestimated the dampening role of schooling. Keynes’s “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” forecast 15-hour weeks by 2030; we turned that slack time into longer schooling instead. Actually, maybe 2030 is right on time. There may not be as much human labor to go around by 2030!

The fundamental principle they both indexed on—that machine substitution would permanently dislocate human labor—is what we’re seeing. The greatest proxy for this is the question (and data) how quickly is human cognition becoming irrelevant?

Geoffrey Hinton, the Nobel-laureate “Godfather of AI” famously said “The past industrial revolutions made human strength irrelevant, this one will make human intelligence irrelevant.”

In economic terms, the labor market is about monetizing two things: dexterity and cognition.

We already see that low level human cognition is becoming full commoditized. Now the question becomes, “What’s the last bastion of human labor?”

We can glean clues from the Attention Economy and the Meaning Economy.

When you “economize” something you are “coordinating the use of scarce resources with multiple uses.” In the case of human dexterity and cognition, we are the jack-of-all-trades. Our hands and brains can do just about anything, hence the labor market economizes jobs.

The Attention Economy, however, is coordinating the scarcity of “eyeball-minutes on screen”—every YouTuber, Substacker, TikTokker, and influencer of all stripes is competing for your time and attention. There are only so many viewers online, and only so many hours per day. The fact that we are competing for you is why you get so much for free.

The Meaning Economy has a huge overlap with the Attention Economy, in that your time and attention are scarce resources. But the service that I’m selling, as part of the Meaning Economy, is sensemaking and meaningmaking—something I hope remains predominantly human (though I personally get more and more of my sense and meaning from AI!)

My advice, in the face of all this, remains the same: learn communication skills.

I’ll add to that list:

Learn to speak to strangers, on a stage, navigate difficult conversations.

Learn how the social brain works, networks, rhetoric, and narratives.

Learn how to be fully in your body, particularly with other people.

With any luck, the one-two punch of AI and robotics will force us to have a social reset. The Great Reset, the Great Decoupling, the Great Displacement, the Great Awakening—whatever you want to call it—times are changing and if we do this right, we might all enjoy a “back to basics” kind of lifestyle.

Sources:

Global Job Displacement

Autor, Dorn & Hanson (2013–2016) — The China Shock

→ Found that U.S. lost between 2–2.4 million jobs from China trade integration 1999–2011

→ Displacement effect plateaued post-2010 as import penetration stabilized

→ Autor’s 2021 follow-up shows fading marginal impact of trade on labor markets.

Peters et al. (2018) — The Rise of Offshoring and its Labor Market Impacts

→ Estimates that offshoring to low-wage countries accounted for roughly 20–25% of manufacturing job losses from 1980–2005

→ Reinforces the idea that globalization was front-loaded: strongest effects pre-2010.

OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) data

→ Shows that by ~2011, foreign value-added share in U.S. final demand plateaued, supporting the “trade effect saturates” idea.

Automation Displacement

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

→ Shows GDP per capita has more than doubled since 1980, inflation-adjusted.

→ Yet median real wages have been mostly flat since the 1970s.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI)

→ Regularly publishes the “productivity vs pay” chart

→ Between 1979 and 2020:

Productivity grew 61.8%

Hourly compensation grew just 17.5%

→ The gap explodes post-2000, consistent with your “automation curve” accelerating around 2010.

Labor share of income falling:

→ U.S. labor share of GDP declined from ~65% in 1970 to ~58% in 2020 (IMF, BLS)

→ Capital-biased tech is the leading explanation—automation replaces labor faster than it augments it.

Acemoglu & Restrepo (2018) — Robots and Jobs

→ 1 industrial robot per 1,000 workers reduces employment by 0.2–0.25 percentage points, and wages by 0.3–0.5%

→ These effects are local and compounding—especially harsh in blue-collar regions.

Education Inflation

First & Second Industrial Revolutions (late 1700s–early 1900s)

Mechanization of agriculture steadily displaced farmhands.

In 1800, ~80% of U.S. employment was in agriculture; by 1900, this had dropped to ~40%.

By 1950, it fell to under 15%—a stunning transformation driven by the tractor, cotton gin, and mechanized harvesters.

Common School Movement (1830s–1870s): Expansion of basic literacy and numeracy.

Compulsory schooling laws (Massachusetts 1852 → nationwide by 1918) were partly a labor absorption mechanism for idle rural youth.

Post-WWII / GI Bill boom

GI Bill of 1944 led to a surge in college enrollments:

Over 7.8 million veterans used it for education by 1956

Transformed college from elite luxury to mass expectation

This began the bachelor’s degree as default era.

Citations

Claudia Goldin & Lawrence Katz, The Race Between Education and Technology

USDA: 20th Century Farm Policy & Labor Trends

Bound & Turner (2002): Going to War and Going to College

Youth Unemployment Canary

Every major technological phase shift leads to a spike in youth joblessness:

1890s–1920s: rural youth pushed into cities for factory work

1950s–1970s: suburban sprawl and office jobs emerge

1980s–2000s: rise of “internship era” and credential creep

Modern equivalent: “failure to launch” narrative

Young adults now delay work, marriage, and home ownership because entry-level employment increasingly demands mid-20s levels of schooling

In 2023: Youth (16–24) unemployment was officially ~8%, but underemployment was much higher. Nearly 45% of college grads are in jobs that don’t require a degree (EPI, NY Fed, 2023)

Technological Frontiers

In the past, when labor markets tightened, displaced youth could move to new frontiers:

1800s: Westward expansion

1900s: Factories, then corporate offices

Today there is no geographic or economic “away” left to run to.

Graduate education has become a refuge from economic irrelevance:

In 2021, ~40% of U.S. grad students said they pursued higher education due to lack of good job options

Median earnings of PhDs now overlap with BA holders in many fields (humanities, education, biology)

Credential inflation has become a holding pattern, not a ladder.

Citations:

BLS & NCES education employment stats

Strada/Gallup: Why People Go to Grad School (2021)

NY Fed: Labor Market for Recent College Graduates

Paul Tough, The Inequality Machine

Some good points. As the father of two boys, 11 and 12, I don't think there's been a harder time on how to guide them in their education. Similarly to when my generation got calculators and thought what's the point of learning arithmetic, they are saying what's the point of learning grammar and writing when LLMs can already do it better than 95% of the population. Tricky times...

So, I’ve done some research. The bad news is, it’s not necessarily about the degree, it’s about the individual. During Covid, those with zero integrity or ethical standards would plagiarize and cheat during exams. They scammed their way through college exams and degrees and it shows in employment numbers. Now, this isn’t a counter argument, it’s true that many degrees become automated which makes things harder for employers and HR departments to deal with because the same people who might be vetting the transcripts and the overzealous resume might be those same folks who cheated and plagiarized themselves into a job. And those who know, don’t want the lawsuits latter on. So, yes, a degree is worthless, unless you can prove to your employer you’re qualified and capable.