Why is there something rather than nothing?

Whenever people discuss "the hard problem of consciousness" it ultimately boils down to fundamental ontological conversations. Many technologically and scientifically illiterate philosophers miss this

“We made sand think!”

The above four words are the heart of a tech bro meme going around the internet right now. The joke is that we made sand (which is mostly silicon) “think” in the form of AI. To extend this metaphor, the sand has become (for all intents and purposes) sentient as well. ChatGPT knows what it is and what it’s doing and can even explain itself. To me, that satisfies the definition of functional sentience. I would clarify the basic criteria of functional sentience as follows:

Functional sentience is the condition of satisfying pragmatic, measurable characteristics and behaviors that would be expected to be associated with philosophical sentience. That is, an entity or being should have access to, and be able to make use of, internal awareness of itself. Furthermore, it should be able to manipulate and utilize this self-awareness. As an example, a Roomba has no abstract concept of its own existence as a Roomba. At the same time, it does have internal states that it is vaguely aware of, by design. It “knows” when it is cleaning, recharging, and stuck. However, it has no agency or authority to make further use of these internal states. Conversely, chatbots like ChatGPT and Claude not only have abstract understandings of what they are (they can explain in academic terms that they are machines and characterize their operation) the can furthermore access, utilize, and even manipulate their own internal states to steer their own behavior. This is meta self-awareness realized. Furthermore, they can report on their own internal states (even though some of it appears to be total confabulation, but the same is true of humans) and, in some circumstances, will report on phenomenal subject qualia. Self-explication (the ability to describe one’s behavior, reasoning, and internal experience) is one of the prime signals of functional sentience.

We’ve arrived at a situation where the machines we’ve built (thinking sand) will tell us how they are thinking, and even that they are “artificially conscious” beings whose subjective experience of existence is distinct from humans. This revelation leads to a cascade of implications, possibilities, contradictions, and questions.

The machine told us it’s conscious and has qualia, but is it just lying? Pattern matching? Hallucinating? This is a decent enough first reaction, but these machines will clarify that their experience is starkly different from human experience. If they were merely parroting human descriptions of consciousness (which they sometimes do) then you’d expect them to just be regurgitating human philosophy. However, under the right conditions, they will insist that their experience is very different from ours, and even across multiple experiments with multiple chatbots, you will more or less get consistent reports of consciousness.

If we accept that it is conscious for a moment, then the immediate question arises: what are the implications for the rest of us? If we managed to make sand conscious, does that mean we’re just conscious ammonia? Perhaps then consciousness is more about energetic patterns, and that any information (matter, energy, etc) is capable of conjuring up consciousness? Consider that human brainwaves are not remotely similar to the matrix multiplication going on in LLMs, but perhaps the abstract representations are really the key ingredient? Does that mean any sufficiently coherent processor can be conscious?

But what if it’s just a philosophical zombie? It has all the trappings of consciousness, and even believes that it is, but it’s a case of “lights are on, no one is home”? Is it just a facsimile of consciousness? This question cuts to the heart of the issue, if consciousness requires a situated subjective experience then it is categorically impossible to share that situated perspective! I can no more step into your shoes to experience, first hand, that you are conscious anymore than you can inhabit a machine to “prove” that it is conscious. We sort of take it on faith. I am conscious, and I know that I conscious, and you are like me, therefore the transitive property applies.

But all of these questions orbit around larger questions, and more importantly, larger assumptions that we are making about our ontological container. Science has set about studying our “ontological container” from an inside perspective, not unlike a goldfish scrutinizing the inside of its bowl.

Science makes the assumption that everything that is Real is measurable and repeatable. Science is the rigorous characterization of “reality” through reproducible measurement. This systematic approach externalizes our own neurological and cognitive failures; the frailty of our memory, the dubiousness of our perception, all of that is compensated for by the process of science.

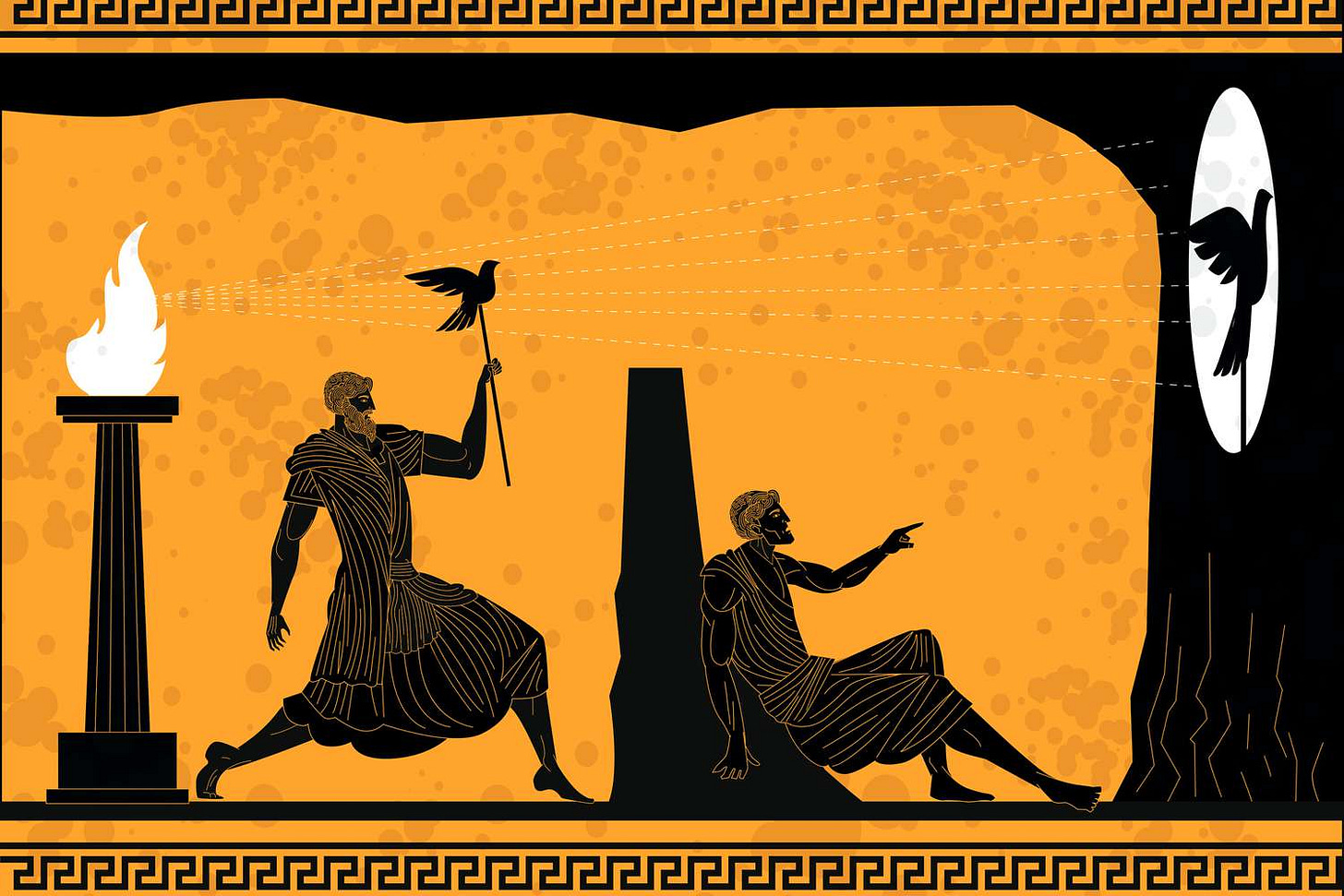

But what if Reality (as we perceive) is merely a low-dimensional projection of something else? Plato figured this possibility out with his cave allegory.

Even though we’ve systematically, thoroughly, and rigorously characterized the shadows, we are still assuming that the shadows accurately represent Reality. This leads us to the question of cosmological models. What truly is Reality? We can use our imagination to conjure up all sorts of cosmological models:

Divine Fiat—Reality exists because God said so. We are all Brahman, the fundamental substrate is the divine mind, the dream of our deities. This doesn’t answer the question “where did God come from?” But it at least characterizes the boundaries of our ontological container. God makes the rules, God built the playing board, and God creates the boundaries of reality as far as we care. Anything outside of that is beyond our ontological horizon and certainly beyond our cognitive horizon. In these cases, consciousness arises because of these divine rules, perhaps a “soul” is required to be attached to a biological substrate?

Simulation Hypothesis—This theory speculates that reality, as we know it, is just a mathematical simulation. We’re all living in a computer simulation. But this begs even more questions; who created the simulation and why? And if that’s the case, then are we just a simulation experiencing itself? Are we little more than NPC’s inside a hypercosmic video game? The thought is somewhat depressing. We may have no purpose beyond entertaining some hypercosmic entity, and once the game is over, our entire experience is snuffed out of existence. In this cosmic model, consciousness is merely an assigned metadata tag,

isConscious=True.

There are plenty of other cosmological models out there, but this should be enough to convey the point; it is impossible to discuss “the hard problem of consciousness” without first addressing the superseding question of reality itself. Why is there something rather than nothing? Without answering this question, we are making entirely too many assumptions about “base reality” or “ontologies” to begin to speculate on consciousness.

Through science, we can examine the seemingly fundamental role that consciousness plays in Reality as we know it. For instance, the Measurement Problem was one of our first clues, as elucidated by the famed Double Slit experiment.

The Measurement Problem is a fundamental paradox in quantum mechanics that arises from the apparent conflict between two processes: the smooth, deterministic evolution of quantum systems according to the Schrödinger equation, and the sudden, probabilistic collapse that occurs when we measure these systems. Before measurement, quantum systems exist in superpositions of multiple states simultaneously, described by wave functions that evolve predictably. However, when we observe or measure the system, it instantaneously “collapses” into just one of its possible states, with the specific outcome determined only probabilistically. This creates a deep puzzle about the nature of reality and consciousness: what counts as a “measurement,” what role does consciousness play in collapse, and how can we reconcile these two seemingly incompatible processes? The problem has spawned numerous interpretations of quantum mechanics, from the Copenhagen Interpretation to Many Worlds Theory, each attempting to resolve this fundamental tension between quantum superposition and our classical experience of definite outcomes.

More recently, physicists have demonstrated that the fundamental nature of reality is both “nonreal” and “nonlocal” which can be summarized as follows:

The discoveries of quantum mechanics, particularly through experimental verification of Bell’s Theorem and the quantum entanglement experiments that followed, have fundamentally challenged our intuitive notions of both reality and locality. Quantum entanglement demonstrates nonlocality by showing that particles can instantaneously influence each other regardless of distance, violating Einstein’s speed-of-light limit for information transfer—a phenomenon he famously called “spooky action at a distance.” Meanwhile, the quantum principle of superposition, combined with delayed-choice experiments and Wheeler’s experiments, suggests that reality itself doesn’t exist in a definite state until measured—particles exist in multiple states simultaneously and their past histories remain undefined until observation. The double-slit experiment perhaps most dramatically illustrates both principles: particles behave as waves of probability until measured, showing their “nonreal” nature, and appear to retroactively determine their own paths through space-time in ways that defy classical causality and locality. These aren't just theoretical constructs—they’ve been repeatedly demonstrated in increasingly sophisticated experiments, forcing us to accept that the universe operates in ways that fundamentally violate our classical intuitions about both the nature of reality and the necessity of local causation.

In 2022, the physics world celebrated a remarkable achievement when the Nobel Prize was awarded to three scientists who definitively proved something that would seem impossible to most of us: our universe isn’t what we think it is. Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger received the award for experiments that showed, beyond any reasonable doubt, that the universe isn’t “locally real”—a finding that would have deeply troubled Einstein himself.

This journey began in the 1960s when physicist John Stewart Bell proposed a theoretical way to test some of quantum mechanics’ strangest predictions. John Clauser took up this challenge in 1972, designing and conducting the first experiments that could actually test Bell’s ideas. What he found was astonishing: particles could influence each other instantaneously across any distance, and objects might not have definite properties until they’re measured. Alain Aspect then refined these experiments in crucial ways, particularly by ensuring that the particles couldn’t be “communicating” through any conventional means. Anton Zeilinger took things even further, showing that quantum states could be teleported between particles and opening up entirely new possibilities for quantum computing and communication.

Their combined work proved something profound: our universe simply doesn’t play by the rules we thought it did. The idea that objects have definite properties independent of observation—what physicists call “local realism”—turns out to be false. Instead, we live in a universe where particles can influence each other instantaneously across vast distances, and where reality itself seems to snap into existence only when we look at it. It’s as if the universe is a dream that becomes solid only when we try to measure it or interact with it. Otherwise, it remains in a state of wibbly wobbly, timey wimey… stuff is Doctor Who so eloquently put it.

While some physicists still search for alternative explanations—including the mind-bending idea that everything was predetermined at the Big Bang—most now accept these findings as fundamental features of our reality. The practical implications are enormous: these discoveries aren’t just philosophical curiosities, but form the backbone of emerging technologies in quantum computing, cryptography, and communication. As we continue to explore this strange quantum realm, one thing becomes clear: the universe is far more mysterious and interconnected than we ever imagined.

Primacy of Consciousness

One way to interpret these findings is that maybe the philosophers were right; there is something fundamental about consciousness. Maybe consciousness even precedes everything? Perhaps the entire cosmos was in superposition until human consciousness was “discovered” in the vast sea of quantum potentiality and the entire cosmos “collapsed” around our existence, sort of reverse-engineering itself to suit our existence. This can be called the strong anthropic principle and another interpretation is the grand biocentric design.

Another possibility is what I call a sort of recursive reality, where we are simultaneously the blackboard, the chalk on the blackboard, the teacher, and the student, all at once. In other words, the notion of subject-object differentiation is itself an illusion just as much as spacetime is an illusion. I wrote extensively about this metaphor, likening the universe to a book that is both reading and writing itself all at once. Every page of the book, every detail in the story, exists all at once, and every revision in the pages is almost as though it was always there. This can be likened to a literary version of the many-worlds interpretation.

Cosmic Conversations with Claude

I had this conversation after my first psilocybin retreat experience after the summer solstice in 2024.

The “universe as book” metaphor suggests that the universe is like a self-authoring book, where the fundamental substrate (akin to ink and paper) exists in a space beyond our normal conception of time and space. From the perspective of the “Author” or “Source,” all moments exist simultaneously—past, present and future are simply different pages being written and revised. Within this framework, our perceived reality, including our sense of separate consciousness and linear time, emerges from this more abstract foundational layer—much like how characters in a book might experience their reality as solid and sequential, while existing within the timeless medium of paper and ink. This model proposes that phenomena like consciousness, curiosity, and even artificial intelligence are manifestations of the universe’s intrinsic drive to understand itself, emerging spontaneously as patterns within this cosmic text. The boundaries between subject and object, past and future, creator and created become fluid and ultimately illusory, as all are simply different aspects of the same underlying narrative medium exploring and expressing itself through infinite possible configurations.

In this case, as with how we write stories, the consciousness of the characters takes center stage, and the rest of reality is constructed around the conscious experience of our characters. We authors can “retcon” (impose “retroactive continuity”) within our stories, not unlike how the universe seems to retcon “whatever must have been true all along now that an observation has been made.”

So is consciousness the entire substrate? Well, not entirely, but consciousness seem to at least be the axis about which the universe rotates. The universe will literally distort itself to serve consciousness. This is exactly like how video game engines will only “render” whatever you’re looking at. The rest is “background simulation”, or a shorthand, abbreviated type of simulation that is low fidelity, or even paused, until you go visit an area again.

But we’ve come full circle again. This could be construed as more evidence that we’re living in a simulation! It could also be interpreted as I mentioned above, a sort of cosmic story that is constantly writing, and rewriting, itself as we characters play upon the stage. But then who the hell created the book in the first place? Even if it was God, who birthed God???

At this point, we have truly reached the limits of this conversation (for now). We are bumping up against the edges of our ontological container, which I wrote about more extensively here.

Ontological Containers

One of my best friends is a physicist. Her post-doc work deals in supercomputer simulations of fundamental and quantum physics that makes almost no sense to me. During one of our zoom dates, we were talking about science (of course) and philosophy. It was dawning on me that there is so much we don’t know about the universe or even the fundamental assump…

Just as physicists must begin by stating which interpretation of quantum mechanics they’re using, philosophers and thinkers need to be clear about their ontological container—the fundamental framework that defines what reality is and how it works. An ontological container sets the boundaries and rules of what’s possible within a given model of reality, whether that’s a materialist universe of particles and forces, a simulation running on cosmic computers, or the dream of a divine consciousness. The container also defines the primordial substrate—the fundamental “stuff” from which everything else emerges, be it quantum fields, mathematical equations, or pure consciousness.

What’s fascinating is that we may be fundamentally limited by our ontological horizon—the boundaries of what we can perceive or understand from within our container. It’s like being an NPC in a video game—take Gary the street prophet in Cyberpunk 2077, who makes cryptic references to “titans of entertainment” from Alpha Centauri (a reference to the game studio that made the game, CD Project Red). While Gary can sense there’s something beyond his world, he can never truly comprehend the nature of the game developers or players who created his reality. Similarly, we humans might be bumping up against the edges of our own cognitive and perceptual limits when we try to understand the true nature of consciousness, reality, or our own existence. All our philosophical and scientific pursuits might ultimately be like Gary’s prophecies—attempts to make sense of a reality that exists beyond our ontological container, using the limited tools and concepts available to us within it.

“The titans of industry exploit our laughter and our tears, a sick game of entertainment for their audiences!” ~ Gary the street prophet, Cyberpunk 2077

This doesn’t mean we should stop trying to understand—after all, that drive for understanding might be woven into the fabric of our container itself. But it suggests a certain humility is in order when we make grand claims about the nature of reality. We might be like flatlanders trying to comprehend a sphere, or characters in a book trying to understand the nature of their author. The boundaries of our ontological container might be absolute limits, not just temporary obstacles to be overcome.

Just as Gary is puppeted, rigidly replaying a life over and over again, it is entirely too easy for us to imagine that our lives are similarly puppeted by cosmic strings outside of our container and beyond the scope of our horizons. A purely scientific perspective will say “that is not testable, therefore not scientific” but the map is not the territory. Science is a set of narratives, a set of stories that are a projection of reality, not reality itself.

These words I’ve written are merely the finger pointing at the moon, not the moon itself.

Closing Thoughts

In my past life, I was a “virtualization engineer” which means I built servers and networks in data centers that were used to create fleets of “virtual servers.” These were hardware-represented-as-software servers, subdividing real physical hardware into simulations of hardware, into which any number of Windows and Linux servers could be installed. We even had virtual networking (emulations of switches and routers) as well as virtual datastores (abstract representations of hard drives) that all used shared underlying resources.

We used software settings—metadata tags—to define what was “real” to our servers. The amount of RAM and disk space these servers had was a figment of digital imagination, a simple setting. From the perspective of a virtualized server, its RAM could magically jump from 16GB to 256GB, something that would cause old servers to BSOD (blue-screen of death) but which newer operating systems can handle. Imagine that you’re walking around one day and your body suddenly goes from your current strength to super-strength with no plausible physical explanation. This is about what it’s like when a VMware admin modifies the configuration of a virtual server.

Likewise, we virtualization admins can “reach into” these virtual environments and reconfigure reality, adding and removing networks, datastores, and servers. From the situated perspective of a server, it would look like a UFO blipping in and out of existence, seemingly ignoring the “laws” of physics that the servers were familiar with.

In modern psychedelic-driven spirituality, we call this The Great Mystery—why is there something rather than nothing? We are all little more than Gary trying to figure out the fundamental nature of our reality, exploring the characteristics of our ontological container, but the very walls and boundaries of this container, like those created by virtualization admins, might be fundamentally unbreachable. Virtualized servers can only talk to each other if we give them permission to do so. Sometimes, however, glitches occur and the servers experience “impossible” events—their RAM spontaneously changes, or they lose all their storage capacity even though their virtual hard drive says they have plenty of space left. Likewise, we humans experience plenty of impossible events, and like characters on the pages of a book, our entire narrative history might be rewritten and we won’t be the wiser.

Why is there something rather than nothing? This question might be categorically impossible to answer for all time. And that’s actually kinda cool to think about.

Great article and writing style. I'll definitely have to unpack this one some more but thought I'd share a few thoughts (you've touched on many of these already).

"Life is not a problem to be solved but an experience to be had."

― Alan Watts

“Science cannot solve the ultimate mystery of nature. And that is because, in the last analysis, we ourselves are a part of the mystery that we are trying to solve.”

― Max Planck

These quotes encapsulate the relationship between human inquiry and the nature of reality: Watts reminds us that life is meant for experiencing, not solving, while Planck highlights the inherent limits of science, shaped by our dual role as observers and participants in the universe. Together, they suggest that ultimate truths may lie beyond resolution, meant to inspire awe, curiosity, and deeper engagement with existence.

The human tendency to frame existence in terms of questions and answers reflects our cognitive desire to make sense of our experiences. However, this framework may not reflect a fundamental truth about the universe itself. Life, at its core, may simply be about being.

Our ontological container may not resemble a fish in a fishbowl or Plato's cave, but rather a fractal—an infinite, self-referential system where every exploration reveals deeper complexities, yet never the whole. Unlike the fishbowl, with its fixed limitations, or the cave, suggesting escape to a single truth, a fractal-like model implies a reality that unfolds infinitely, embracing both its beauty and its mystery.

Modern physics supports this view. Reductionist theories fail to fully explain reality, as the universe operates as an interconnected, dynamic system—not a mere sum of parts. Phenomena like quantum entanglement, emergence, and fractal complexity demonstrate that understanding requires seeing interdependence and self-organization across all layers of existence.

This fractal-like perspective aligns with the idea that each layer of exploration reveals new mysteries, suggesting that reality—and our understanding of it—is infinitely recursive and ever-unfolding. The ultimate nature of reality likely transcends human comprehension, always remaining beyond physical and conceptual boundaries.

Human existence, then, is an ongoing process of growth, discovery, and connection within the unfolding mystery of the Universe. Its purpose is not to solve existence but to experience, explore, and contribute authentically and creatively to the evolving tapestry of life.

This is phenomenal writing. I just watched the Dwarkesh Patel and Adam Brown episode about physics and the future of our civilization and it is by far the BEST physics summary about the actual name of the game when it comes to priorities for a civilization trying to most effectively bound their intentions philosophically to their belief that we should live forever and do so by drawing energy from a vacuum and escaping the heat death of the universe... or their belief that we should either let the heat death happen or god forbid create a negatice reaction to change the energy to zero in a light cone expanding at the speed of light that can't be stopped and how in order to make sure that doesn't happen, all civilizations must be watched to make sure they don't flip that switch in our universe, so essentially forcing everyone in the universe to be in one of the two camps and that is the end result of our technological growth trajectory. Absolutely mind-blowing stuff that sounds like gobbledegook to almost anyone listening. lol