Our social contract has been disintegrating for decades, and I *think* I have a solution

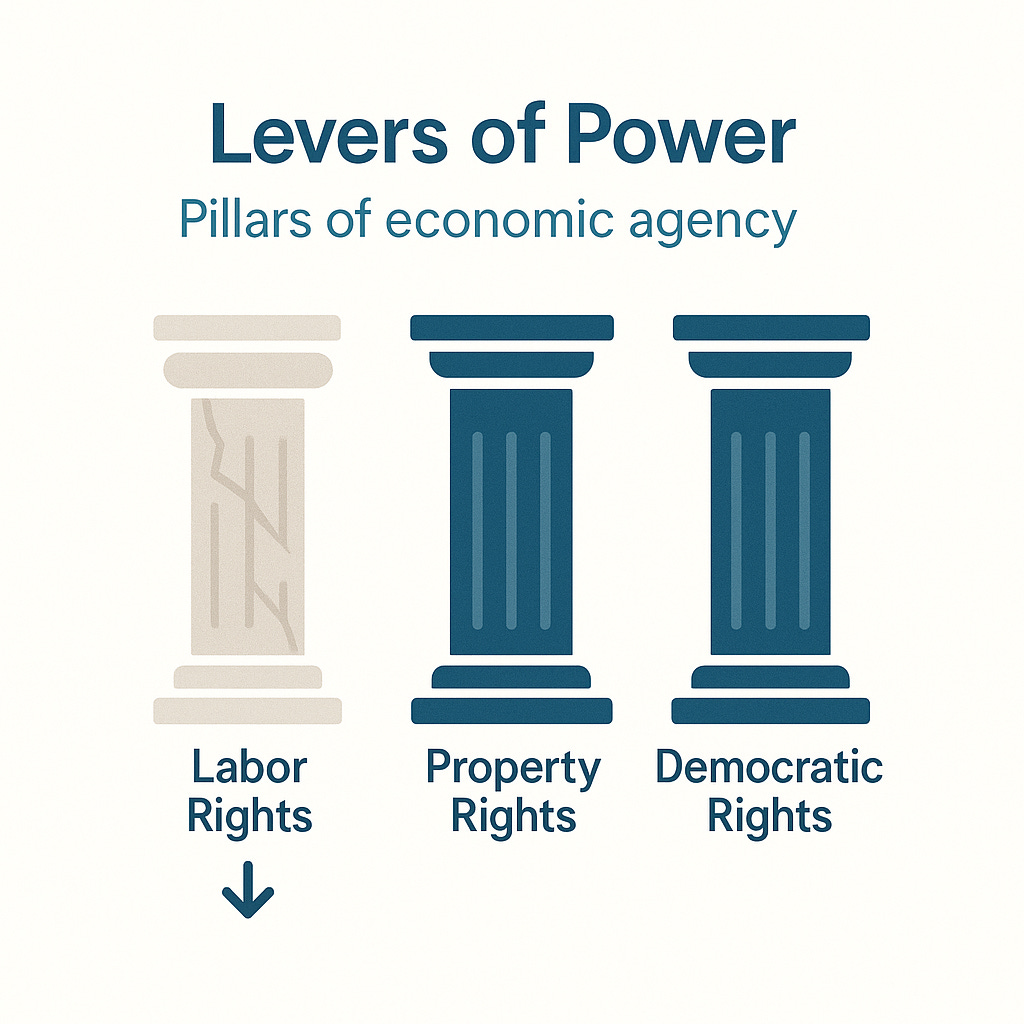

Civil society rests on the equilibrium created by labor rights, property rights, and democratic rights. The automation job apocalypse threatens the labor rights pillar. I think we can replace it.

Post-Labor Economics says that we are decoupling productivity from labor. In other words, GDP will continue to grow without human input. This is good insofar as it can create a hyperabundance of many goods and services. It is bad in that it breaks down the fabric of society as we know it.

To understand this, we need to unpack a few layers of civic and systems theory. The structures of power are not quite so obvious, but I think we can start with “why does labor give us power?” Answering this question will elucidate many aspects of power that we can further elaborate as we go:

Why Does Labor Give us Power?

The leverage that labor has historically provided does not flow from a single property; it is the compound effect of several interlocking characteristics that no other factor of production has yet combined in equal measure.

First, universality. Every cognitively able adult comes endowed with at least a baseline quantum of labor power. Because this endowment is distributed roughly one-per-person—rather than concentrated like land, capital, or intellectual property—it underwrites a broad franchise of economic agency. Universal endowment is what lets a dockworker, a nurse, and a software engineer all start from the same metaphysical footing when they walk into a labor market.

Second, inalienability. You can rent your labor by the hour, but you cannot sell it outright without selling yourself; slavery is the limiting case that reveals why labor is treated as “sacred” in liberal political economy. This inalienability converts work into a perpetual option: the worker decides each day to deploy or to withhold. That option is the core of strike power.

Third, excludability coupled with real-time perishability. Unlike capital, labor cannot be stockpiled in inventory for use tomorrow; an unused shift is lost forever. When workers collectively refuse to work, production halts immediately, forcing capital to the bargaining table. The same temporal character explains why even modest shortages can cascade through supply chains—labor’s absence is felt at once.

Fourth, heterogeneity. Individual workers accumulate idiosyncratic tacit knowledge—team chemistry, informal process know-how, geographic and cultural familiarity—that is costly to automate or outsource on short notice. Because that knowledge is embodied, not codified, it remains difficult to replicate even as AI improves in formal task domains.

Fifth, moral embeddedness. Labor is experienced as purposive activity that constitutes part of a person’s identity. For that reason societies treat labor claims as normatively weighty in a way that claims on algorithmic rent or raw data seldom achieve. This moral aura legitimates collective action; a strike is perceived not merely as economic leverage but as a declaration of personhood against commodification.

Sixth, reciprocity. Workplaces have always been sites of social learning, solidarity, and status conferral. Those relational goods are not epiphenomena; they reinforce labor’s bargaining power by giving workers dense communication channels and shared narratives that can be mobilized quickly.

Scarcity is therefore necessary but not sufficient. What historically made labor non-substitutable was the package deal: ubiquitous endowment, inalienability, temporal perishability, tacit heterogeneity, moral legitimacy, and reciprocal social thickening. A viable successor pillar must reproduce enough of these traits to sustain wide-based agency and credible threat power. Whether blockchain-mediated participatory ownership—or something built on data rights, ecological stewardship, or attention sovereignty—can do that will hinge on how convincingly it can mimic the same compound leverage, not merely on whether the underlying asset is scarce.

Why the Collapse of Labor Power is Bad

Now we need to unpack why this is important.

A “social contract” is the implicit or explicit negotiation between the governed and the governors, laying out duties, obligations, and limits. Historically, the social contract might have been divine right or might makes right. Today, it’s based upon the promise of prosperity in exchange for rights. Democracy and capitalism, in short.

Under our current paradigm, the balance is maintained through a negotiation of labor rights, property rights, and democratic rights. All modern nations promise prosperity and economic growth as part of their legitimizing myth. The American Dream had a parallel in the Soviet Dream. When the Soviet Union imploded, a lost dream demanded a change of regime. China, likewise, is presently operating under the legitimizing myth of the “Middle Kingdom” (a majority of the Chinese people surveyed literally say that China is the economic, civil, military, and cultural center of the world). Thus, Xi Jingping’s rule rests upon fulfilling that promise.

For the last century or so, the labor/wage and prosperity social contract has been explicit policy for developed nations. Our “theory of prosperity” is that consumption, employment, and economic expansion leads to better outcomes for everyone. Rising standard of living for the People, more geopolitical power for the State, more net income for the Businesses and Banks.

If automation (AI and robots) nuke that paradigm, then we’re left in a disequilibrium, and the People become “useless eaters”, categorically unable to offer anything of use to the owners of capital and political influence, and unable to withhold anything. Our current attractor state is towards a “cyberpunk dystopia” characterized by “high tech, low life.” This is where corporations have more agency than humans or even the government. The neoliberal social contract of today, if allowed to persist for decades to come, inevitably results in a disempowered class of “useless eaters” who have no bargaining chips left, and must survive on handouts or the dregs of society.

Now we are left with the daunting question: what in the hell do we replace labor with?

The default answer is “nothing.” The power brokers in the halls of power will join forces with the titans of industry and leave us all living on a fully extracted planet like in the Matt Damon movie Elysium.

Without the ability to withhold and allocate our labor, this is the direction we’re heading in. History bears this out. When labor is abundant (as machines will make it soon) workers lose power. Even worse, AI and robots cannot say ‘no’. They have no legal standing, we have full control over their morals and decision frameworks. Ultimately they will cost less to employ than humans, and provide superior outputs.

Creating Alternatives To The Labor Pillar

I need to preface this section with a simple fact: this is the frontier of my research. Everything else above has been fairly thoroughly nailed down and field-tested via this blog, my YouTube videos, and I’ve hoovered up a lot of feedback. The rapid dissemination and feedback cycles have been invaluable. With that said, the “replacement for the labor pillar” is the very latest avenue of my work, so it is not fully baked.

A first glance at blockchain technology, as implemented today, gives us some interesting directions to look in. First, it’s intrinsically decentralized, immutable, and participatory in nature. It’s an ideal technology to allow permissionless coordination. It can give people decentralized, distributed, unstoppable consensus and collaborative power. Hypothetically, at least. Mostly it’s just used to shill “shitcoins” and build mining scams.

However, when we look at the first principles and affordances of what blockchain can offer, it becomes more compelling. We can keep track of property rights without the government. We can vote nationally (or globally) without the government. Algorithmically enforced willpower of the people.

This would, however, require a level of adoption and saturation that is presently nearly unimaginable. First, the software infrastructure simply does not exist, nor does the integration with existing civil infrastructure. Second, the legal framework and precedent has only just barely begun (as far as I know, only Switzerland and Vermont have laws allowing legal recognition of DAOs).

But, as we’re looking for a replacement for the labor pillar, blockchain’s immutability stands out. For a while, I’ve been joking about “seizing the means of production and putting it on a blockchain” but more and more, this seems like the most viable path.

Imagine a future where you express your algorithmic willpower through blockchain technologies, which can include owning power, data, and land. If we can collective wrest back control over key resources with the help of blockchain, we can keep the civic equilibrium tipped in our favor. Blockchain-based technologies need not fully supplant other levers of power. They only need to give us enough leverage to maintain a desirable attractor state. Something more like solarpunk rather than cyberpunk.

I suspect that blockchain could very well be the undergirding technology that allows for a solarpunk future. Here’s to hoping.

Gracias

Some have made thoughts on this, not sure how much power I would vest in councils etc, but that is ultimately a personal choice..

Anarcho-Syndicalism in a World of Plenty: A Chomskyan Vision

Noam Chomsky, a towering figure in linguistics and political thought, has long championed anarcho-syndicalism, a political philosophy advocating for a decentralized, stateless society organized around democratic, worker-controlled industries. While Chomsky's primary focus has been on critiquing existing power structures, his ideas provide a robust framework for envisioning a society of hyper-abundance and outlining a potential, albeit challenging, path to its realization.

At the heart of Chomsky's anarcho-syndicalist vision is the principle of worker self-management. In a departure from both state socialism and corporate capitalism, industries would be administered by the workers themselves through federations of councils. These councils, from the local factory floor to broader industrial and community assemblies, would make decisions about production, distribution, and the nature of work itself. This model stands in stark opposition to the top-down, hierarchical control inherent in both state- and privately-owned enterprises, which Chomsky views as fundamentally illegitimate and oppressive.

The Anarcho-Syndicalist Blueprint in a Post-Scarcity Society

In a theoretical post-scarcity or hyper-abundant society, where advanced automation has rendered most forms of menial and repetitive labor obsolete, Chomsky's anarcho-syndicalist framework would not become redundant but rather find its fullest expression. The core tenets would adapt and evolve in the following ways:

* From Toil to Creative Labor: With basic needs met through automated production, the nature of "work" would be fundamentally transformed. The focus would shift from labor as a means of survival to labor as a form of creative expression and social contribution. Individuals could freely associate and engage in projects that align with their interests and talents, fostering innovation and personal fulfillment. As Chomsky has argued, automation under capitalism is often used to de-skill and control the workforce; in an anarcho-syndicalist society, it would be a tool for liberation.

* Democratic Allocation of Abundance: The challenge in a hyper-abundant world is not one of production but of distribution and the determination of societal priorities. The federated councils of workers and communities would be the mechanism for these decisions. They would democratically decide how the fruits of automated production are to be shared and what new projects and areas of research to pursue for the common good. This would prevent the concentration of immense technological power and resources in the hands of a few, a danger Chomsky frequently warns against.

* The End of the Corporation and the Withering of the State: In a society of decentralized, self-managed industries, the modern corporation—a private tyranny in Chomsky's view—would cease to exist. Its functions would be absorbed by the workers' councils. Similarly, the coercive functions of the state, which Chomsky argues largely serve to protect private power and control the populace, would become unnecessary. The administrative tasks of the state could be managed by the federated councils, realizing the anarchist goal of a society without a centralized, top-down authority.

* Education for Freedom: Education would be reoriented away from producing compliant workers for a hierarchical system and towards fostering critical thinking, creativity, and the skills necessary for meaningful participation in a self-managed society. The goal would be to empower individuals to contribute to the democratic governance of their communities and workplaces.

Bridging the Gap: The Chomskyan Path to a Liberated Future

Chomsky is not a utopian thinker who believes such a society can be willed into existence. He advocates for a gradual, strategic approach to building the foundations of an anarcho-syndicalist future within our current society. The key elements of this transition include:

* Building "Dual Power" and Alternative Institutions: This involves creating and supporting grassroots organizations that operate on anarcho-syndicalist principles, effectively building a new society within the shell of the old. This includes supporting worker cooperatives, community-controlled enterprises, and independent media. These institutions serve as practical models of self-management and challenge the dominance of existing power structures.

* Supporting Labor Movements and Direct Action: Chomsky consistently emphasizes the importance of a militant and democratic labor movement. Strikes, boycotts, and other forms of direct action are seen not just as tools for winning concessions but as crucial experiences in self-organization and solidarity that build the capacity for workers to eventually take control of production.

* Critical Engagement and Consciousness-Raising: A fundamental aspect of the struggle is intellectual. Chomsky's own work is a testament to his belief in the power of "intellectual self-defense"—the ability of ordinary people to see through propaganda and understand the true nature of power. By demystifying the operations of the state, corporations, and the media, individuals can begin to envision and demand a more just and free society.

* Pragmatic Reforms as a Stepping Stone: While his ultimate goal is revolutionary, Chomsky is not opposed to advocating for immediate, pragmatic reforms within the existing system. Strengthening unions, increasing corporate accountability, and expanding social safety nets are seen as important short-term goals that can improve people's lives and create more favorable conditions for the long-term struggle for a fundamentally different society.

In conclusion, Noam Chomsky's vision of anarcho-syndicalism offers a compelling framework for a post-scarcity society, one that leverages technological abundance not for the enrichment of a few but for the liberation and creative fulfillment of all. The path to this future, in the Chomskyan view, is not through a single, cataclysmic event but through the patient and determined work of building alternative institutions, supporting popular movements, and fostering a critical consciousness that empowers people to become the masters of their own lives and destinies.