Technology does NOT create new jobs!

Wages and labor demand have been declining for decades due to automation. Automation creates new job titles, but in aggregate, it creates a net loss of jobs. This is a new economic paradigm.

“Technology always creates new jobs!”

No, it does not.

While in nominal terms, yes, technology has created new jobs (cloud data center engineers didn’t exist in the 1950s!) there has not been a commensurate rise in the total number of jobs as you’d expect, proportional to population. Furthermore, there is now ample evidence that technology broadly (and automation specifically) has been eating into the demand for human labor, causing commensurate drop in wages as well as overall employment.

None of these data are obscure or arcane, I have simply scraped them together from disparate sources, and they all point in the same direction; while automation might create new job categories, it absolutely does not create proportionally more jobs in absolute terms.

These data have been corrected for trends such as offshoring and globalism. Even when you account for jobs lost overseas, we are still hemorrhaging jobs faster than can be explained without blaming automation. If prevailing economic theory were true, we’d expect the opposite; that secondary and ancillary jobs would be increasing, not decreasing.

One final thing we need to understand before looking at these charts is this; the numbers do not have to trend to 0% or $0 before the current social contract breaks down. Furthermore, these historical data do not necessarily anticipate or account for automation shocks (rapid dislocations and shocks). Our entire point here is to disabuse you of any notion that technology automatically increases aggregate demand for human labor (it does not).

Each graph will serve as a header, with the subsequent paragraphs unpacking the graph. Sources for all data cited at the end.

The Historical Data

Labor’s share of non-farm business income fell from the 63–65% plateau of the post-war decades to around 56–58% in the 2010s, a multi-decade nadir; globally the labor share slid from 53.9% in 2004 to 52.3% in 2024.

The long-term erosion of labor’s share of non-farm business income—from a stable post-war plateau around 64% to barely 57–58% in recent decades—signals a fundamental shift in the distribution of economic value. This decline is not cyclical noise but structural dislocation: over the same period, productivity rose steadily, yet the median worker saw little to no real wage growth. In effect, the marginal returns on human effort have decoupled from overall output gains. The proceeds of economic expansion have increasingly flowed to capital—in the form of profits, rents, and intellectual property—rather than to the broad base of workers. The global data echo this trend: from 2004 to 2024, labor’s global share slipped from 53.9% to 52.3%, indicating that this is not a parochial American anomaly but a system-wide feature of advanced capitalism in the digital-automated age.

The mechanisms behind this displacement are manifold but mutually reinforcing. First, capital-biased technological change—especially in automation and software—has substituted machines for routine human tasks at a pace faster than labor can reallocate to new functions. Second, globalization has expanded the effective labor pool, exerting downward pressure on wages in tradable sectors. Third, institutional supports for labor have withered: union density has collapsed, the real minimum wage has decayed, and collective bargaining has lost its teeth. Meanwhile, the rise of superstar firms and intangibles-heavy business models has amplified returns to scale without proportionally increasing headcount. In sum, the declining labor share reflects not a shrinking pie but a new rulebook for dividing it—one that no longer assumes human labor as the default engine of value capture.

The divergence between productivity and pay since 1979 represents perhaps the most distilled expression of labor’s declining claim on economic output. According to BLS and EPI analysis, non-farm business sector productivity—measured as output per hour—has increased by approximately 86% from 1979 to 2023. Over the same period, hourly compensation for production and nonsupervisory workers rose only about 32% in real terms. This implies that productivity has grown approximately 2.7 times faster than typical worker pay. In a world where compensation tracked productivity, median earnings today would be dramatically higher; instead, the gains have been captured elsewhere—by owners of capital, high-income professionals, and technological intermediaries.

This decoupling occurred for structural reasons. Until the mid-1970s, productivity and compensation moved in tandem, enforced by institutional mechanisms—strong unions, binding minimum wages, and norms of wage compression. After 1979, that compact unraveled. Labor market institutions weakened, global competition intensified, and technological change began to favor capital-augmenting innovations—robots, software, platforms—that scale without hiring. At the same time, corporate governance shifted to priorities shareholder value, flattening wage structures and offloading risks onto contract and gig workers. The result is a labor market that still generates output, but no longer treats wage growth as a necessary or even expected corollary.

Automation—encompassing both physical machinery and digital software—has been the central enabler of this divergence, fundamentally altering the production function of modern firms. Since the 1980s, successive waves of technological substitution have displaced human labor in routine, codifiable tasks across manufacturing, clerical work, retail, logistics, and more recently, professional services. Capital-biased technological change, by its nature, raises output per worker without requiring a proportional increase in labor input, thereby inflating productivity statistics while suppressing aggregate wage bills. The increasing computational power of software, the scalability of cloud infrastructure, and the rise of algorithmic decision-making mean that vast swathes of value can now be generated with minimal human intervention. This not only weakens the bargaining position of remaining workers—since their marginal product is harder to distinguish from the machine’s—but also concentrates income in the hands of those who own or control the enabling technologies. In effect, automation has functioned not merely as a substitute for labor, but as an institutional bypass around it.

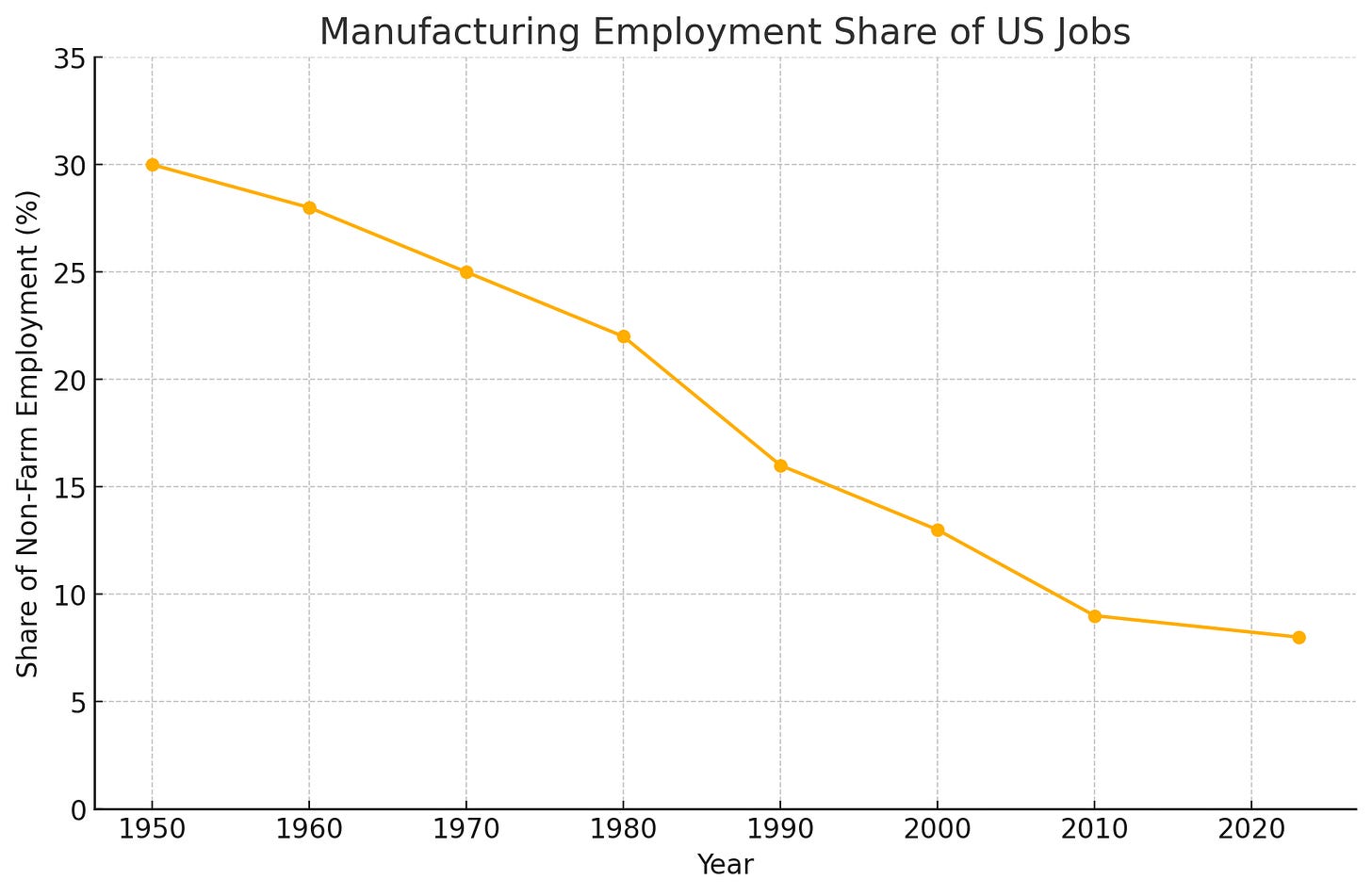

The collapse of manufacturing employment in the United States—from a peak of 19.6 million jobs in 1979 to roughly 12.7 million today—despite continued growth in output, is among the most unambiguous illustrations of labor displacement through automation and structural change. In 1953, nearly one-third of all non-farm employment was in manufacturing; today that figure is closer to 8–9 %. This disjuncture between rising output and falling headcount reveals a deep decoupling: factories are producing more goods with fewer workers, a direct consequence of the capital-deepening process. From robotic assembly lines to just-in-time logistics and computer numerical control (CNC) machining, technological progress has rendered many mid-skill, repetitive manufacturing roles obsolete—not by offshoring them, but by eliminating their necessity altogether.

The drivers of this displacement are both technical and institutional. Technically, automation in manufacturing is especially tractable: tasks tend to be routine, spatially fixed, and governed by standardized processes—all ideal conditions for robotic substitution. Moreover, digitization has enabled continuous process optimization, with sensors and software making production lines adaptive and self-correcting. Institutionally, the erosion of union power and the deregulatory turn of the 1980s and 1990s made it easier for firms to adopt labor-reducing technologies without facing meaningful resistance or needing to share the productivity gains with workers. The outcome has been a bifurcation: high-output, high-efficiency manufacturing exists, but it is capital-intensive and lean on jobs. For the broader economy, this has hollowed out the middle of the labor market, severed one of the key escalators of upward mobility for non-college workers, and intensified regional economic divergence between deindustrialized communities and knowledge-heavy metro hubs.

The collapse of union density in the United States—from over 33 % of the workforce in the 1950s to around 10 % today—represents not just a shift in workplace organization, but a wholesale weakening of labor’s institutional leverage. This erosion has occurred in tandem with wage stagnation, falling labor share, and rising inequality, all of which unions once counteracted through collective bargaining and standard-setting. While automation and capital intensification certainly exacerbated the decline—by rendering certain categories of manual and routine labor structurally redundant—they did not cause it in isolation. Rather, they operated within a political framework that actively disempowered organized labor.

Since the late 1970s, a deliberate policy regime—commonly described under the rubric of neoliberalism—has tilted the playing field against collective bargaining. “Right to work” laws, restrictions on card check and organizing drives, aggressive employer tactics backed by weak penalties, and a judiciary increasingly skeptical of labor rights have all conspired to institutionalize labor’s precarity. In this context, automation did not merely replace workers—it replaced unionized workers under the aegis of a regulatory order designed to suppress wage floors and fragment worker solidarity. The substitution of capital for labor thus became not only an economic efficiency but also a political strategy. Without unions, the gains from productivity growth—especially when driven by machines and software—accrued almost exclusively to capital, further reinforcing the asymmetric feedback loop between technological change and wage suppression. The erosion of unions, then, is not simply a consequence of automation; it is a precondition that made automation’s wage-displacing effects politically and institutionally viable.

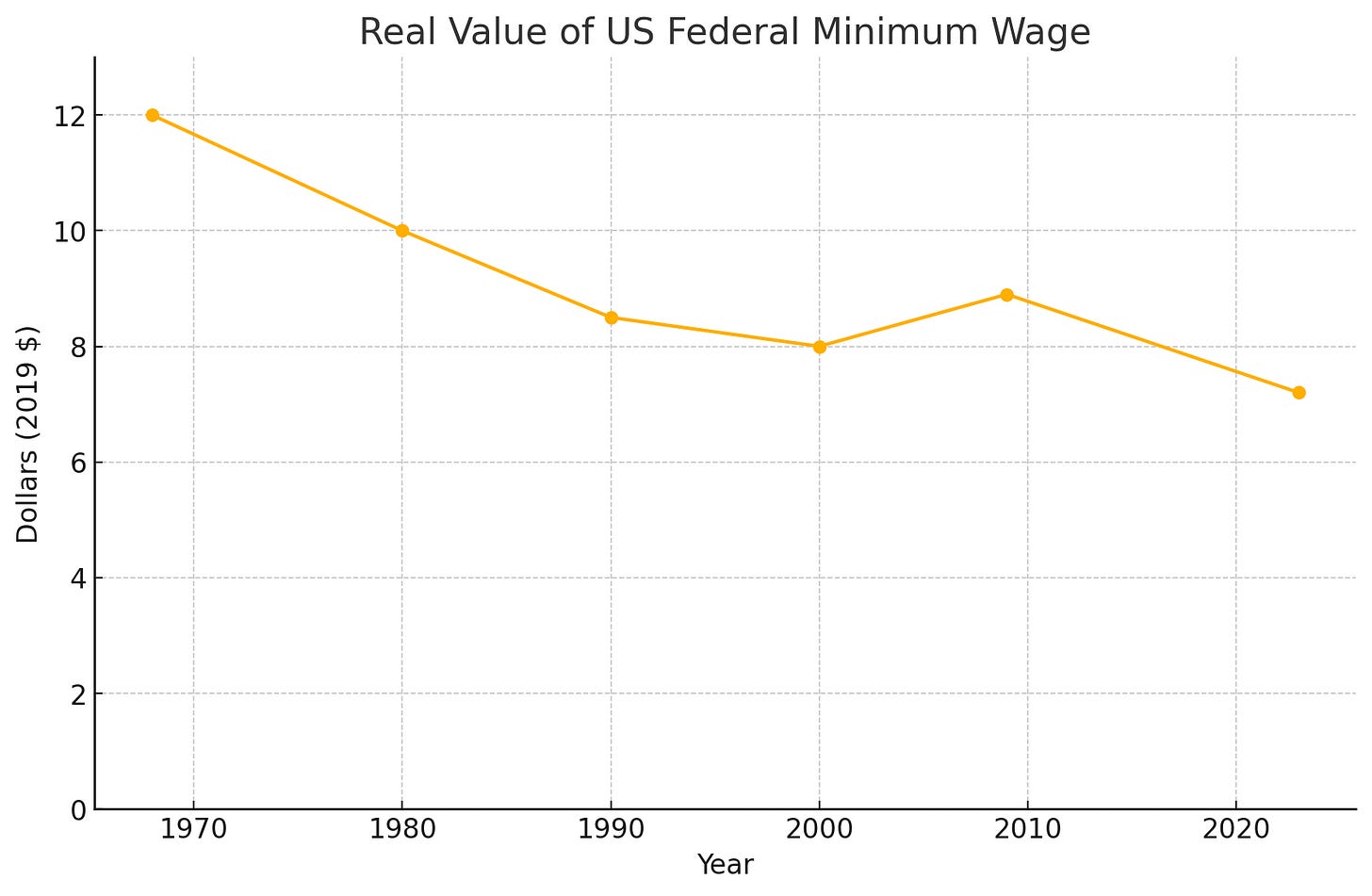

The erosion of the federal minimum wage—now $7.25 per hour, unchanged since 2009—reflects a profound institutional failure to preserve the wage floor in line with either inflation or economic growth. Adjusted for prices, today’s minimum wage is approximately 40% below its 1968 peak in real terms and 27 % below its own inflation-adjusted value from just over a decade ago. This decline is not the result of market forces, but of legislative inaction: Congress has simply refused to raise the floor, even as the cost of living and average productivity have steadily climbed. In effect, the real minimum wage has become a shrinking guarantee—eroding its role as a safeguard against poverty and a stabilizer of low-end wages.

This institutional decay intersects directly with broader dynamics of automation and capital deepening. As low-skill labor becomes more substitutable—either by machines, software, or offshored labor—the bargaining power of those at the bottom of the wage ladder is further weakened. Employers face less pressure to raise wages when technology or non-union contract labor offers a cost-effective alternative. But the erosion of the minimum wage is not just a market reaction; it is also an ideological project. Since the 1980s, economic orthodoxy has argued that wage floors distort employment and reduce efficiency. Under this logic, a stagnant or declining minimum wage became a policy choice: it enabled greater “flexibility” for capital, maintained low-cost labor pools for service sectors, and reinforced the broader disempowerment of low-wage workers. The result is an economic order in which the minimum wage no longer anchors the bottom of the labor market, but instead recedes in relevance, increasingly symbolic rather than functional.

The decline in prime-age male labor-force participation—from approximately 98% in the mid-1950s to around 88–89% today—represents one of the most enduring and understudied structural changes in the American economy. This is not a cyclical artifact: the rate falls during recessions but never fully recovers, ratcheting downward over time across expansions. These are men aged 25–54—the demographic historically considered the backbone of the industrial workforce—now increasingly absent from formal labor markets. A ten-point drop in participation over seven decades translates into millions of missing workers, individuals who are neither employed nor actively seeking work. The implications are not merely economic but social and political: such persistent withdrawal from the labor market reshapes family structures, erodes community stability, and contributes to the broader sense of economic dislocation.

The causes are complex and interlocking. Automation plays a significant role by hollowing out the demand for mid-skill, mid-wage roles—precisely the kinds of jobs that once anchored male employment in manufacturing, transport, and clerical sectors. As routine-intensive tasks are increasingly absorbed by machines or software, the opportunity structure for non-college-educated men has narrowed dramatically. Globalization and offshoring compounded this, displacing industrial work and weakening wage ladders. At the same time, institutional changes—such as the decline of unions and the stagnation of real minimum wages—have reduced the incentives and bargaining power to remain attached to marginal employment. Moreover, the rise in disability claims, especially in areas suffering from industrial decline, has provided an exit path from the labor market for many men with limited prospects. This is not always fraud or malingering; it often reflects genuine injuries or chronic conditions that render physically demanding work untenable in a labor market with little room for adaptation. Taken together, these forces constitute a structural reconfiguration: not simply fewer jobs, but fewer socially legible and economically viable roles for a growing share of prime-age men.

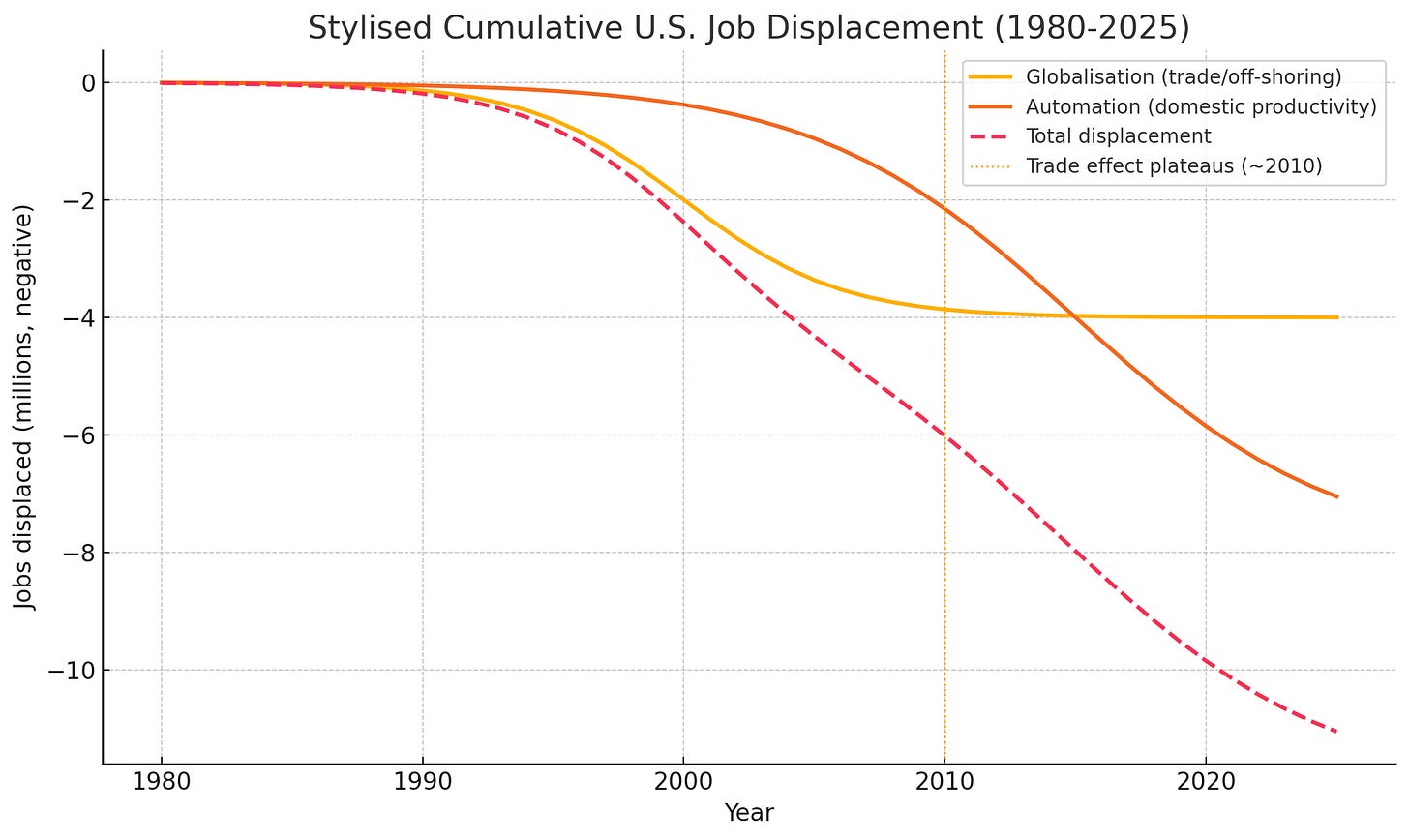

This graph—adapted from research by economist David Autor, among others—visually dissects the cumulative job displacement in the U.S. since 1980 into two principal drivers: globalization (via trade and offshoring) and automation (via domestic productivity growth). It shows that while trade shocks, especially the China import surge post-2001, led to substantial early job losses (≈ 3–4 million by 2010), this effect plateaued as trade imbalances stabilized. In contrast, automation-driven displacement has intensified, continuing to absorb labor demand even as globalization’s direct impact flattened. The result is a total displacement figure exceeding 10 million jobs by 2025, the majority attributable not to foreign competition but to domestic capital deepening.

This finding reinforces what Autor has called the problem of the “missing millions”—workers who did not merely shift to new sectors after industrial contraction, but vanished from the labor force altogether. His work demonstrates that even after controlling for offshoring and trade exposure, large swaths of mid-skill employment never rematerialized. Automation, rather than simply reallocating labor, erased the economic functions once performed by humans, especially in routine-heavy roles like assembly, clerical processing, and logistics. Unlike trade, which redistributes jobs geographically, automation shrinks the total number of human job slots. And because this displacement is continuous and endogenous—driven by technical progress and declining capital costs—it is not self-limiting. The implication is profound: policy responses that focus solely on trade adjustment assistance or re-shoring will miss the deeper, structural cause of labor displacement. The challenge is not just global competition, but technological redundancy, compounding over time and removing the economic necessity of millions of workers.

Conclusion

The inevitable conclusion from evaluating these data is simple: technology does not, in aggregate, “always create new jobs.” Quite the opposite. We’ve seen a long, steady, multidimensional erosion of demand for human labor and a commensurate decline in wages. While there are some cofounding variables at work, such as demographic shifts and globalization, these alone do not fully account for the “missing millions” of new jobs we’d have expected to be created. Many of these trends are hidden under normalized and nominal values, such as raw GDP growth (which you would expect GDP to decouple from labor inputs in an automated economy, exactly as we’ve seen) as well as the huge population growth, which lifts employment in absolute terms.

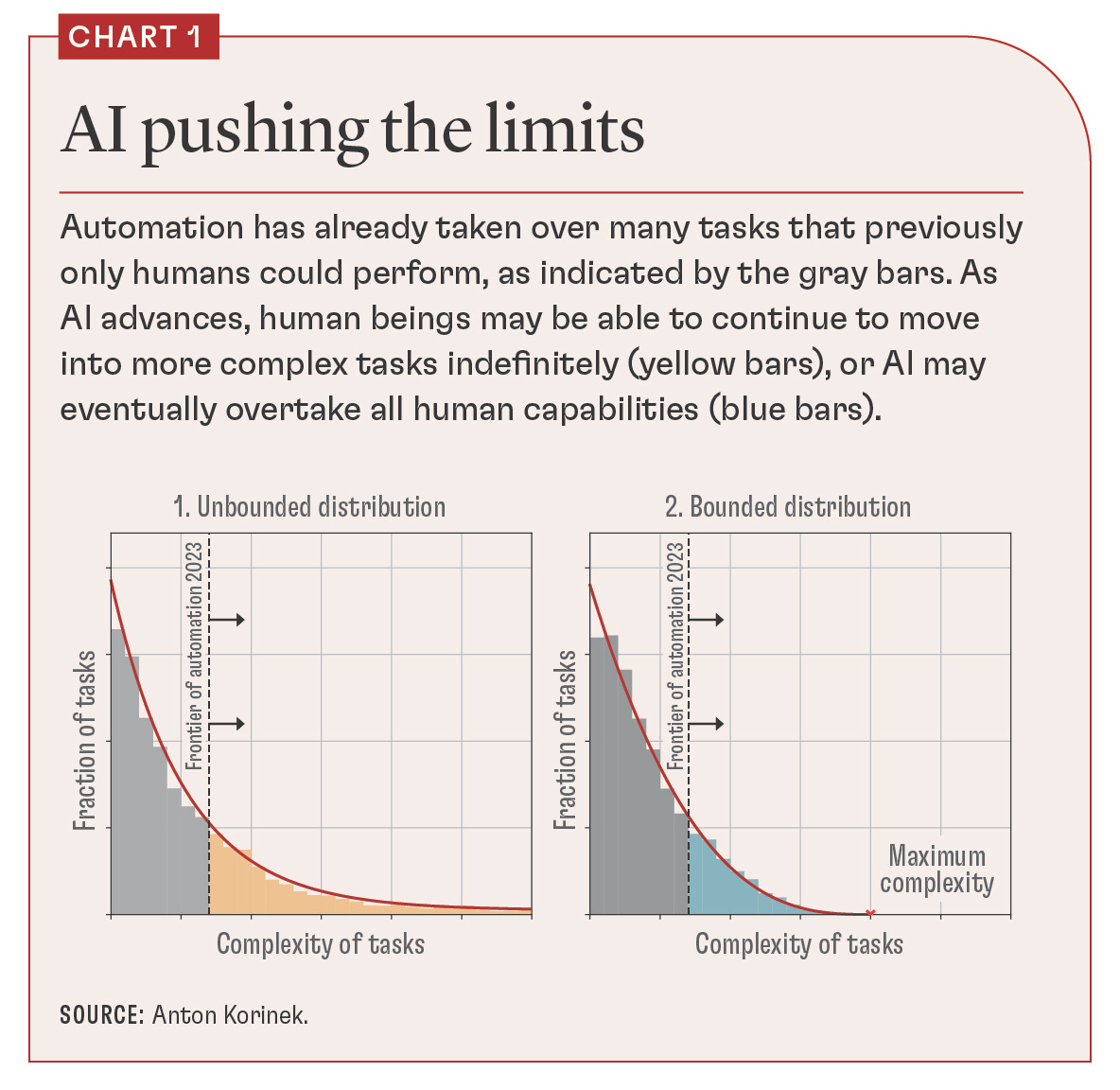

Political forces, such as the rise of neoliberal theory, have certain “squeezed” the middle class by eroding labor union power and favoring globalization. But even that systemic shift in policy does not fully explain the erosion of wages and labor demand. Furthermore, the rise of AI and humanoid robotics will merely expand and accelerate the frontier of automation. The sphere of human-preferable jobs will continue to shrink, so far as we can tell, indefinitely. It may reach an asymptote, but that value will be much less than what we see today, and this will invariably leave many millions of people in the lurch, without any possibility for jobs.

Therefore, we must create a new social contract that is more participatory.

Sources

• Labor-force participation (prime-age, male and total) – Current Population Survey micro-data as aggregated in BLS series LNS11300061 (men 25-54) and LNS11300060 (all 25-54); published monthly in Employment Situation – Table A-7 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

• Manufacturing employment levels and shares – Current Employment Statistics (CES) series CEU3000000001 (manufacturing jobs) and CEU0000000001 (total non-farm payrolls), Bureau of Labor Statistics.

• Labor share of non-farm business income – Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 1.14 “Gross value added of non-farm business” combined with BLS Hours & Compensation data; the integrated series is disseminated by BLS Productivity and Costs (Major Sector) release.

• Productivity versus typical compensation – BLS Major Sector Productivity index for output per hour (non-farm business) and BLS average hourly compensation for production-and-nonsupervisory workers (series CES0500000008); the divergence series popularized by the Economic Policy Institute uses these two official inputs.

• Real federal minimum wage – Nominal minimum from U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division “History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates” deflated with BLS Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

• Union membership rate – BLS annual Union Membership data, derived from CPS supplement “Characteristics of Union Members,” series LUU0204899600.

This is a very insightful and meticulous piece. Thanks for another Shapiro 💎

Cheers

Thanks for writing. Great article as usual. Doomers are either clickbaters or their victims. Im not an economist but its obvious that if automation can replace jobs which leads to exponential profits then of course those jobs will be cut. Robots are already replacing jobs everywhere.

Not only low wage jobs but people who make $500k as surgeons and specialists. Millions of people will not have to be cogs in the wheel. Human brains do not exist to be cogs. Finally, technology will allow all the cog life to go away. There will be unbelievable productivity. Trillions of dollars and tens of millions of displaced workers obviously means a completely different economic and perhaps political system.

The average person cannot wrap their heads around this and think there will just be millions of people hanging out on the stoop once the jobs are gone. That's just mypoic. Thats applying 2030 technology to 2025 economics. Everything will change.

Will there be cybercrime? Sure. Machines dont commit crimes, though. People do. When they build a destructive agent, there will also be a shield. AI is justnantool, even at the goal of AGI level of computing.

Thank you for all your insights, Dave. Some people already get it. Some people will soon get it. Some never will.