How to Use Epistemic Tribal Theory: TPOT on Twitter

After my post about my theory of epistemic tribes, a few people asked "Okay, so how do you use this in practical terms?" - Here's an example from a new epistemic tribe on Twitter for a case study.

This is going to take some unpacking.

First, there’s a trend on twitter called TPOT, which stands for “This Part of Twitter.” I needed to use a combination of Perplexity and Grok to figure out what this epistemic tribe is:

TPOT, short for “This Part of Twitter,” refers to a loosely defined online subculture and community primarily active on Twitter. Emerging around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, TPOT is characterized by its interest in intellectual discourse, technology, science, and unconventional topics. It has roots in the Rationalist and Effective Altruism movements, but also embraces post-rationalist thinking that includes spirituality and alternative perspectives. TPOT participants value curiosity, openness to new ideas, and a balance between serious discussions and playful interactions. The community lacks formal boundaries or membership criteria, instead signaling affiliation through engagement in nuanced discussions, openness to unconventional ideas, and participation in community events like “Vibecamps.” Notable figures in the TPOT community include Aella Girl, Venkatesh Rao, Sarah Perry, and eigenrobot, though influence within the group is fluid and subjective. TPOT aims to foster an environment for free exploration of ideas without strict ideological constraints, blending intellectual depth with approachability and humor.

Great, so we have the outside view of this epistemic tribe. Interestingly, one of their self-described values is that they are “hard to define”―which really just means they are not conscious of their own epistemic tribal values or grounding referents.

Referent: In the context of epistemic tribes, a “referent” is a value, axiom, belief, or idea that serves as social, intellectual, or moral grounding. In other words, referents are core sets of values and beliefs that define the epistemic tribe. One example could be from Christianity, which has many referents. Some sects of Christianity prioritize Hell i.e. “Hell is real and bad and you go there if you’re bad, therefore you should do everything in your power NOT to go to Hell when you die!”

The existence and fear of Hell perfectly explains the behavior of some sects of Christianity. Prime example below:

Many epistemic tribes resist being put in boxes. “Don’t categorize me!” Some where them loud and proud.

Everything can be categorized. Refusal to be categorized from an inside perspective doesn’t mean there are no referents.

But here’s where a pattern emerged to me. Having studied history and philosophy, I noticed that they are embracing the cornerstone referents of both “optimistic nihilism” (nothing matters so just have fun) as well as postmodernism (there is no truth, only perspectives and deconstructions). They sometimes call themselves “postrats” for “post-rationalist” but this is literally just postmodernism repackaged.

The TPOT community's self-proclaimed “post-rationalism” can be seen as a repackaging of postmodernism and optimistic nihilism, albeit with a tech-savvy, internet-age twist. By moving away from strict rationalism, TPOT members have essentially embraced postmodern ideals of skepticism towards grand narratives and objective truth, favoring instead a playful deconstruction of ideas and a celebration of ambiguity. Their penchant for irony, memes, and fluid, ever-evolving discourse mirrors postmodern approaches to meaning-making. Simultaneously, the community’s apparent embrace of life’s absurdities while finding joy and camaraderie in intellectual exploration aligns closely with optimistic nihilism. The “postrats” may believe they’ve transcended rationalism, but in reality, they've circled back to well-established philosophical traditions, albeit expressed through the lens of internet culture. Their virtue signaling through wit, openness to unconventional ideas, and rejection of strict logical frameworks are not novel concepts, but rather modern manifestations of postmodern thought and the optimistic nihilist’s approach to finding meaning in a potentially meaningless universe. In essence, TPOT’s “post-rationalism” is less a new philosophical stance and more a contemporary, digitally-native expression of ideas that have long existed in philosophical discourse.

Okay great, so through the lens of status games and epistemic tribes, we can quickly characterize an internet tribe. So, even while they often describe themselves as “difficult to define” it’s actually not that hard:

Here's a labeled list of primary referents (core values and beliefs) for the TPOT epistemic tribe:

Intellectual Playfulness: Valuing the exploration of ideas for their own sake, rather than for purely practical outcomes. This manifests in discussions that blend serious topics with humor and wordplay, encouraging creative thinking and novel connections between concepts.

Ironic Detachment: Embracing a stance of wry amusement towards life’s complexities and absurdities. This allows members to engage with weighty topics while maintaining a sense of levity, often expressed through memes and witty commentary.

Openness to Unconventional Ideas: Willingness to entertain fringe concepts, alternative viewpoints, and speculative theories without immediate dismissal. This might include discussions on psychedelics, futurism, or esoteric philosophies, all approached with a mix of curiosity and skepticism.

Memetic Fluency: Valuing the ability to communicate complex ideas through cultural shorthand, often in the form of internet memes or inside jokes. This serves as both a bonding mechanism and a way to signal in-group status.

Meta-Rationality: Moving beyond pure logic to incorporate emotional intelligence, intuition, and awareness of cognitive biases. This involves recognizing the limits of rationality while still appreciating its value.

Contrarian Thinking: Valuing perspectives that challenge conventional wisdom or popular narratives. This often involves playing devil's advocate or exploring counterintuitive ideas for the sake of intellectual stimulation.

Practical Uses of Tribal Theory

#1 - Understanding Irrational Behavior

Thus, we have arrived at “strength #1” of this theory of epistemic tribes and status games. You can quickly evaluate, characterize, and categorize any group, anywhere. This extends beyond internet culture or religious cults. It applies to tribal coalitions that form within organizations such as academic institutions or companies.

Now, in the case of TPOT, the formula is simple: you start with a base of Less Wrong and Effective Altruism, then bake it over time with postmodernism and optimistic nihilism, and out pops TPOT.

This evolution provides a fascinating case study in how epistemic tribes form and evolve around high-status individuals. The Less Wrong community, founded by Eliezer Yudkowsky, initially centered on discussions of rationality and artificial intelligence risk. What makes this particularly interesting from a status theory perspective is how the community's belief structures have become increasingly resistant to outside criticism or empirical challenge.

Consider Yudkowsky’s trajectory: he gained prominence and status through writing extensively about AI risk scenarios, building a community around these ideas on Less Wrong. Status theory predicts that once someone achieves high status within a community based on specific beliefs or predictions, they become heavily incentivized to defend those positions—even in the face of contrary evidence. This isn't unique to Yudkowsky or Less Wrong; it’s a pattern we see repeatedly in epistemic tribes.

The escalation of rhetoric around AI risk within this community perfectly demonstrates this dynamic. As AI development has accelerated without manifesting the specific catastrophic scenarios originally predicted, we might expect a rational updating of beliefs. Instead, we’ve seen increasingly extreme positions, culminating in suggestions as dramatic as bombing data centers to prevent AI development—a position Yudkowsky advocated for on the TED stage.

“If intelligence says that a country outside the agreement is building a GPU cluster, be less scared of a shooting conflict between nations than of the moratorium being violated; be willing to destroy a rogue datacenter by airstrike…willing to run some risk of nuclear exchange if that's what it takes to reduce the risk of large AI training runs.” - Eliezer Yudkowsky, Time Magazine.

This utterly irrational pattern of thought becomes comprehensible through the lens of epistemic tribal theory. When someone’s status and identity become deeply entwined with specific predictions or beliefs, their social brain often overrides their rational brain. The theory helps us understand how someone can start with reasonable concerns about technology and gradually progress to advocating for extreme measures, all while maintaining internal consistency within their tribal framework.

What's particularly instructive here is how tribal dynamics create self-reinforcing cycles, especially in epistemic tribes centered on singular or extremely limited referents. When a tribe's entire identity collapses around a single core belief—like “AI is inherently dangerous” in the case of Less Wrong—it creates a dangerous feedback loop. The fewer referents an epistemic tribe has, the more likely its members are to take increasingly extreme positions to defend that central identity-defining belief.

This pattern manifests clearly in the AI Safety movement, where participants often signal tribal membership by referring to AI exclusively as a “dangerous technology.” This singular focus creates a blind spot toward AI's demonstrated benefits as a productivity-enhancing tool, as acknowledging these benefits might be seen as undermining the tribe’s central referent. The resulting discourse becomes increasingly divorced from empirical reality as tribal members feel compelled to defend their position against any contrary evidence.

This phenomenon extends well beyond AI discourse. Consider anti-vaccine groups or flat earth communities: these are quintessential examples of single-referent epistemic tribes. When someone's entire social status and identity become anchored to a single belief (“vaccines are always harmful” or “the earth is flat, end of conversation”), they become willing to entertain and defend increasingly implausible positions to maintain tribal cohesion. The singular referent becomes a gravitational center, warping their entire epistemological framework. Every new piece of information must be interpreted through this lens, leading to increasingly tortured logic and rejection of contradictory evidence, no matter how compelling.

“The moon landing was faked” is a prime example of a conspiracy theory referent.

However, now that AGI is on our doorstep and it still shows no signs of waking up and murdering everyone, the Less Wrong (rationalist) and Effective Altruist (EA) communities are finding new referents to center on. This sort of cultural evolution of epistemic tribes is nothing new.

There’s a lot of deep references in the last paragraph so let me explain in more academic terms:

The transition from Rationalism to Post-Rationalism within the TPOT community mirrors the shift from Modernism to Postmodernism in 20th-century Western thought, both triggered by confrontations with realities that challenged their foundational beliefs. Just as Modernism’s faith in universal truths and grand narratives crumbled when Western colonial powers encountered diverse global cultures, the Rationalist community’s core tenets were shaken when their predictions about AI’s existential threat failed to materialize, calling into question the validity of their epistemic and ontological frameworks. This parallel evolution reflects a similar crisis of perspective and subsequent paradigm shift. In both cases, a worldview that championed singular, absolute truths gave way to one that embraces plurality, ambiguity, and skepticism towards overarching narratives. Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard’s work “The Postmodern Condition” (1979) articulated this shift in broader intellectual discourse, while the TPOT community’s embrace of “post-rationalism” represents a similar response within the context of internet-age discourse on technology and philosophy. Both movements reflect a move away from rigid, universalist claims towards a more fluid, context-dependent understanding of knowledge and truth, adapting to a world that proved more complex and diverse than their predecessors had anticipated.

As I like to say: history may not repeat itself, but it sure as hell rhymes. People who don’t study history will mistakenly believe that everything is new, novel, and original. But I digress, that was a tautology.

#2 - Building Stronger Tribes

The transformation of the rationalist community into the “post-rationalist” or “postrat” movement offers valuable lessons in how epistemic tribes can evolve towards greater resilience and wisdom. This evolution wasn’t merely incidental—it was a necessary adaptation when reality failed to conform to their previous models.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” - Richard Feynman

The postrat movement emerged from a profound recognition that mirrored historical philosophical transitions: absolute certainty about complex systems is usually a red flag. Just as the Modernists and Nihilists before them discovered, universal assertions about how the world works tend to crumble under scrutiny. The hubris of claiming complete understanding of complex systems—whether it’s AI risk, geopolitics, or human nature—rarely ages well.

Consider the cognitive dissonance: Here was Yudkowsky, someone with limited expertise in history, military strategy, economics, or international relations, advocating for what amounts to starting a world war to prevent AI development. The post-rats’ cringe at this represents more than mere embarrassment—it’s a healthy recognition of their tribe’s past intellectual overreach.

The Fork in the Road

When epistemic tribes face disconfirming evidence, they typically choose one of two paths:

Double Down: Like Yudkowsky, dig deeper into increasingly extreme positions to defend the original referent. See: flat-earthers, anti-vaxxers, and moon-landing hoaxers.

Evolve: Like the postrats, add new referents and embrace complexity through intellectual humility.

The postrat community chose the latter path, and their evolution offers a masterclass in strengthening tribal epistemology. Rather than maintaining a death-grip on Less Wrong as sacrosanct scripture, they’ve embraced uncertainty and complexity. This isn’t weakness—it’s wisdom. They realized their entire ontological and epistemic model of the world, viewed through the strict lens of Rationalism, might have been fundamentally flawed.

Just as postmodernism emerged when modernist certainties collapsed upon contact with global diversity, the postrats emerged when Rationalist certainties collapsed upon contact with actual AI development.

Building Better Tribes

The postrat community demonstrates how adding multiple referents creates a more robust tribal identity:

Intellectual Playfulness: Replacing dogmatic certainty with curious exploration. In many respects, this better honors the original purpose of the Less Wrong community: “To become less wrong over time.”

Kindness: Valuing human connection over winning arguments. At the end of the day, they implicitly realized that human relationships are a primary source of meaning, and that “being right at all costs” is not a way to win friends.

Epistemic Humility: Acknowledging the limits of our understanding. As previously mentioned, hubristic certainty is a sure sign that you should reevaluate your stance.

Tolerance of Ambiguity: Embracing that many questions don’t have clean answers. As Mark Twain said: “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.”

This multiplication of referents does more than just make the tribe more pleasant—it makes it more resilient and adaptive. When one referent is challenged, the tribe doesn't face existential crisis because its identity rests on multiple pillars.

Practical Applications

Other epistemic tribes can learn from this evolution. The key is proactively developing multiple, reinforcing referents:

Epistemic Referents: How we know what we know, what counts as a “real source of truth?”

Moral Referents: What we value and why, where and how do we define right from wrong? Good from bad? Sources of ethical grounding? This can include things such as teleological or deontological models.

Ontological Referents: How we understand reality; what is the foundational substrate of that which counts as “real”?

Social Referents: How we relate to others; what do we believe about the human race and the human condition? How much do we value relationships, solidarity, and society?

Methodological Referents: How we approach problems? Is internet debate sufficient? Do we need other forms of discourse, such as experimentation and consensus? What is our relationship to data, evidence, and disagreement? Most importantly: how do you resolve cognitive dissonance and internal tension? (no person and no tribe is without contradictions!)

The role of tribal leadership cannot be overstated. Humans naturally gravitate toward charismatic figures, and these leaders set the tone for tribal evolution. When leaders model epistemic humility, curiosity, and nuanced thinking, they create space for the tribe to develop these qualities.

The result? A more robust, flexible, and ultimately useful epistemic tribe. One that can engage with reality on reality's terms, rather than trying to force reality into predetermined boxes. This is the path forward for any group seeking to build lasting influence while maintaining intellectual honesty.

Strength #3: The Path to Self-Development

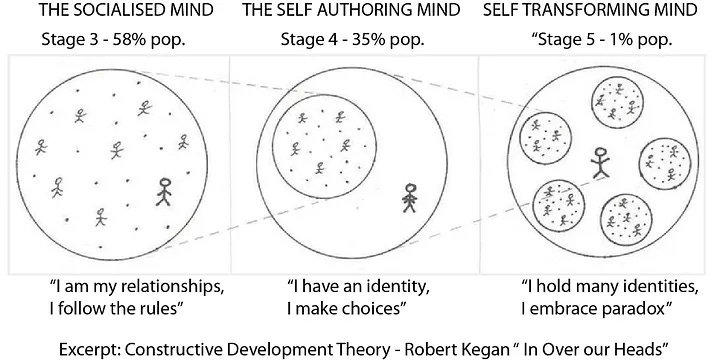

Understanding epistemic tribal theory isn't just about analyzing groups or predicting behavior—it’s a crucial key to personal development. To understand why, we need to explore Robert Kegan’s developmental theory and its profound implications for self-transformation.

“The person with a self-transforming mind is able to see beyond their own ideology or framework, recognizing it as just one possible form of meaning-making among many.” - Robert Kegan

The Stage 5 Mind

Kegan's “Stage 5” or “self-transforming mind” represents a level of development where individuals can step outside their own belief systems and examine them objectively. This isn’t just intellectual flexibility—it’s a fundamental shift in how we construct meaning and understanding. However, reaching this stage requires something that many find deeply uncomfortable: the ability to recognize and temporarily suspend our own tribal identities.

Here’s the crucial insight: You cannot reach Stage 5 without understanding the tribal nature of your own beliefs and referents.

The Myth of Permanent Enlightenment

Many believe that achieving higher consciousness means permanently transcending ego. The science tells us something different:

“The Default Mode Network (DMN) isn’t a bug—it's a feature. Your brain invests significant energy maintaining ego even at rest, because ego serves crucial functions in human consciousness.”

While temporary ego suspension is possible (through meditation, flow states, or psychedelics), it's precisely that: temporary. The goal isn't to eliminate ego but to understand its role in our tribal identities.

The Tribal Resistance to Self-Examination

Warning Sign #1: When scrutiny becomes sin.

Many epistemic tribes actively resist self-examination. Consider:

Religious sects that label questioning as heresy

The original Rationalist movement’s treatment of Yudkowsky’s “Sequences” as gospel (inscrutable and above reproach)

Political movements that cast doubt as betrayal (MAGA)

Social sanction serves as the immune system of tribal beliefs:

Shaming: From the scarlet letters of Puritan New England to modern Twitter pile-ons, tribes have always used public humiliation to enforce conformity. During the Victorian era, women who violated social norms were branded as “fallen” or “loose,” effectively marking them as tribal outcasts.

Bullying: While today we see this most visibly in social media harassment campaigns, bullying has always been a tool of tribal enforcement. Medieval communities would throw rotten vegetables at wrongdoers in the stocks, a public spectacle of tribal punishment.

Excommunication: The Catholic Church perfected this technique, formally cutting off “heretics” from the community of believers. The Amish practice of Meidung (shunning) serves the same function—complete severance from the tribal group for those who question or violate its precepts.

Physical Violence: From tarring and feathering in colonial America to historical witch hunts, tribes often turn to violence to enforce their boundaries. Even today, some traditional societies practice honor killings to enforce tribal norms. Burning at the stake was the original “cancel culture.” (Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition)

Social Ostracism: The ancient Greeks literally voted people out of Athens in a practice called ostracism. Today’s “cancel culture” serves a similar function—the complete rejection from social and professional spheres for violating tribal norms. It’s a nonviolent form of execution. The Klingons call it discommendation.

Throughout history, tribes have used these tools to maintain ideological purity. Understanding this pattern helps us recognize it in modern contexts—from cancel culture to academic ostracism.

The Meta Perspective

Once you understand tribal theory and status games, you gain the ability to see apparently irreconcilable differences through a new lens. Consider these "opposing" tribes:

Geopolitical: West vs. China, Israel vs. Palestine

Religious: Competing claims about divine truth

Academic: Conflicting models and paradigms

Cultural: Traditional vs. progressive values

Enter Metamodernism

Here's where we transcend both modernist certainty and postmodern relativity. Metamodernism offers a crucial insight: These tribal conflicts aren't evidence that “nothing is true” (postmodernism) or that “only one truth exists” (modernism). Instead, they’re emergent phenomena—predictable patterns arising from numerous underlying systems.

“The map is not the territory, but understanding how different tribes draw their maps helps us navigate the territory more effectively.”

Breaking the Stage 5 Barrier

The reason so few people reach Kegan's Stage 5 isn't due to genetic limitation or superior cognitive ability. It's simply because we haven't had a coherent theory explaining how these pieces fit together. Metamodernism, combined with tribal theory, provides this framework.

The path to Stage 5 requires:

Recognition of your own tribal identities

Understanding of how referents shape belief systems

Ability to temporarily suspend tribal allegiances

Integration of multiple perspectives without losing coherence

Application of this meta-awareness in daily life

This isn’t just theory—it’s a practical path to higher development. By understanding the tribal nature of human meaning-making, we can transcend our default modes of thinking without denying their utility or reality.

Conclusion: The Reality of Human Nature: A Case Study

Let me share a revealing moment from a guest lecture I gave in an applied ethics class at Duke University. The topic was predicting future human behavior through data analysis and understanding human nature. During the Q&A, I received a thoughtful challenge:

“If human nature is fixed, how do you explain the documented decrease in violence over time?”

It’s a compelling question, especially if you’re working from a simple epistemic model. The data does indeed show a decline in violence over centuries—and if that’s your only reference point, you might reasonably conclude that human nature is malleable and progressively improving.

But then reality intrudes.

Consider the events of October 7th, 2023, and its aftermath: the Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s subsequent response. Both demonstrated that humans remain capable of profound violence under certain conditions. This isn’t ancient history—this is now. This is us. We must always contend with our capacity for profound violence and inhumane treatment of each other. After all, our ancestors who were more ready, willing, and able to defend their existence with violence passed on their genes. Violence will always be within the realm of possibility for humans.

“The arc of history bends toward justice, but only if we maintain the institutions that enable that bending.” (and as my wife points out, the arc of human history is not linear, nor without setbacks)

The Metamodern Resolution

Through a metamodern lens, this apparent contradiction makes perfect sense. What we’re observing isn’t a fundamental change in human nature, but rather the emergence of systems and institutions that successfully suppress our capacity for violence. These systems—stable governments, reliable food and shelter, rule of law, democratic processes—create conditions where violence becomes unnecessary and costly. It’s all about incentive structures: the cost of violence is far greater in modern democracies, but when those institutions fail, baser behaviors reassert themselves.

There’s the crucial insight: Remove these systems, and human nature reasserts itself.

When survival is at stake, tribes will always choose themselves, even if it means violating their own ethical principles. This isn’t regression or barbarism—it’s the permanent condition of human nature, which emerges through our biology and evolution, which themselves emerge from our biochemical substrate. Your tribe might deeply value peace, democracy, and rule of law. But if those options are removed? If it’s survive or perish?

The science supports this view. No tribe fully embodies its highest ideals. Consider:

Academics valuing intellectual humility while fighting viciously over ideas, resorting to theft, perjury, insults, and plagiarism.

Religious groups preaching love and peace while practicing exclusion, ethnical cleansing, and holy war.

Even fictional examples like Star Trek’s Klingons, who valorize honor yet constantly struggle with dishonorable behavior, such as treacherous acts like assassination and betrayal.

The Emergence of Understanding

Metamodernism offers a framework for understanding these apparent contradictions. It views human behavior as emergent phenomena:

Morality and ethics emerge from biology and mind

Biology and mind emerge from physics and chemistry

Epistemic tribes emerge from human social nature

When we view reality through these ontological strata—these layers of existence and emergence—the contradictions resolve themselves. What seemed like cognitive dissonance becomes clear pattern recognition.

This is the power of tribal theory and metamodern thinking: it allows us to step back far enough to see the full picture. The challenge isn't that human behavior doesn't make sense—it’s that we often fail to take a wide enough view to understand it.

Our tribal nature isn’t a bug—it’s a feature. Understanding this helps us build better systems, create more resilient institutions, and perhaps most importantly, maintain the humility to recognize that our highest ideals will always be aspirational rather than achieved states.

I wrote more about ontology here:

Ontological Containers

One of my best friends is a physicist. Her post-doc work deals in supercomputer simulations of fundamental and quantum physics that makes almost no sense to me. During one of our zoom dates, we were talking about science (of course) and philosophy. It was dawning on me that there is so much we don’t know about the universe or even the fundamental assump…

Sources:

THE STATUS GAME by Will Storr

SAPIENS by Yuval Noah Harari

BRAINTRUST by Patricia Churchland

A bunch of books on postmodernism and nihilism (too many to list)

About four or five dozen videos on philosophy, evolution, and more

Countless conversations with friends and my wife

Thank you for unpacking the concept of TPOT. The term was referenced in an article I was reading about the United Healthcare killing in headline that read, “This one internet subculture explains murder suspect Luigi Mangione’s odd politics”

https://sfstandard.com/2024/12/10/this-one-internet-subculture-explains-murder-suspect-luigi-mangiones-odd-politics/

I’m not in a position to evaluate. But, I find it an interesting subculture, nonetheless.

I look forward to reading more of your articles.