How I become an expert* in anything

I used to be pretentious enough to call myself a "transdisciplinary polymath" now I just say I like learning a lot and that I'm an autodidact. Like Socrates, all I know is that I know nothing.

During the last ritual at the psychedelic retreat I went to in June of 2024, I had to confront a deeply personal story, one that was, perhaps, not the best narrative. You see, growing up I was always praised for how smart I was, for how curious and observant. This was not a one-off thing by a stranger or a teacher. It was a constant drip-feed from parents, family friends, teachers, and even peers. This created a personal narrative that intelligence was my power, that it was the best way to get my social needs met, and it ultimately became somewhat performative.

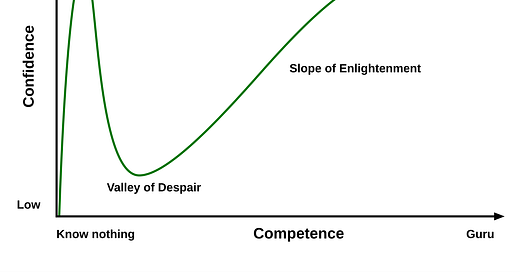

During that last trip, I learned that I couldn’t relax because I felt the need to understand everything. My personal theory of control became “So long as I understand everything, I will have control over my life.” After all, it’s how I made money and it’s how I got famous. But I had to accept confusion and chaos, and my own limitations. I had to become comfortable sitting at the bottom of the Dunning-Kruger curve.

It’s true that I built my IT career on my ability to learn quickly, on the fly, and to self-teach. I did the same with AI and YouTube. Certainly, I think the belief that I am an autodidact is helpful, but recently I’ve been asked specifically “how do you do that?” Because it’s one thing to believe a story about yourself, and it’s another for people to ask about behaviors and results.

Fortunately, I have a good cultural model for staying in the valley of despair and never identifying as an expert. Japanese artisans and craftsman are famously humble. What we westerns would call mastery and excellence, they humbly shake their heads and say “Oh, no, I’m not that good.” Meanwhile, they are making exemplary tools and works of art, with a level of care and precision rarely attained by makers. I won’t go into all the cultural reasons for this, but the point is I have this model that I have adopted.

Here’s a great video about extremely high-end barber scissors made in Japan. This video captures this culture of humility and excellence. In fact, humility is a primary ingredient to excellence. By never identifying as a master, or wrapping one’s esteem up in a sense of excellence, they continuously learn their entire lives.

Okay, that’s great, but what do I actually do to learn things so thoroughly and quickly? I was recently having lunch with a professor who asked me this question, and it took me a while to crystallize an answer. So, without further ado, here’s my simple framework for mastery:

1. Read A Lot

The first thing is that I read. I had the good fortune to marry a librarian, who rekindled my love of learning and validated my curiosity. Here’s some of what she taught me:

Reading a few good books on a topic is enough to make you an expert (so long as they are truly good books!) If you read 3 or so of the top books in any field, you will know more about that subject than 90% of graduates or experts in that field.

More importantly, how to find and identify “good books” which includes media literacy, information literacy, and identifying quality sources. Librarians are fortunately trained in this task.

I also deliberately get books with different views and perspectives on various topics. I think of it as creating a cross-section or X-Ray of a topic.

Finally, I read extremely broadly. Many people have their niche they like, but I take myself out of my comfort zones. I also follow lines of resonance. For instance, when I was trying to understand the fundamental nature of the universe I read everything from string theory to NDEs to Brahman theory. I call this practice circumscription today. AI chatbots can be helpful for this, especially if you ask good follow-up questions.

2. Talk to People

Drinking in information and knowledge from books is great, but this practice alone has relatively little utility. You need to put it into practice, use it, work with it. Mental grist for the mill is like any material. You can fell a tree, turn the timber into lumber, and dry it out. But until you make something with it, it’s just wood. Likewise, until you test and refine your understanding with other people, ideally people in the same space, it doesn’t mean much.

There are plenty of reasons for this. Neurologically, your brain handles internal representations differently when conversing about them. As a social species, our brains light up very differently when we are interacting with other humans. Conversation and dialog does many things, such as forcing information across the corpus callosum, and activates a slew of other brain regions that don’t normally talk to each other when you’re by yourself.

“Conversation is a provable way of making good progress in learning.” ~ Dr. Chi Wang, Microsoft Research

Generally speaking, talking to experts and deeply thoughtful people who are educated on a topic is best. I’m not a fan of debates, but prefer the term dialectics. Many people, particular internet denizens and academics, are locked into prestige status games where it’s more about who’s right and wrong, and there’s a sort of intellectual one-upmanship going on. This is not productive because it basically short-circuits any conversation, once someone “proves” that they are the “authority” and then they stop listening and it becomes a lecture.

Instead, approaching all intellectual conversations with a dialectical intention is better. Debating is so postmodernist. Dialectic is metamodern, baby. Ultimately, what happens is that you synthesize something new. There’s a sort of mental transmutation that takes place via conversation. It’s like intellectual alchemy. The right conversations with the right people will guide you towards mastery.

In fact, I’ve incorporated this method into my Pathfinder community. Today is the last day you can sign up at $19 per month. Tomorrow, and ever after, the price goes up! I use Zoom sessions to have round-table dialectic conversations on topics. We temporarily create a gestalt brain, a sort of miniature superorganism that evolves and changes, depending on who’s present. I can teach the same concept three times and have three fundamentally different conversations. It’s wild. But these conversations transmute my understanding, as well as those of the participants.

3. Communicate It

Just as conversations with other humans is a great way to refine, distill, and crystallize your understanding, so to is teaching. This is something I stumbled on quite by accident via my YouTube channel. Very often, I would want to teach a topic, or discuss a specific concept, but the act of preparing for the video would force me to research it, realize what I was trying to say, and I would have many discoveries along the way. Even further, I would often connect the dots in real-time as I made the videos.

Making slide decks and recording YouTube videos is not the only way to “bake in” these ideas. In point of fact, the entire reason I started this SubStack was merely to be an intellectual dumping ground, like a training arena for new ideas. I had exactly zero intention of using this platform for anything other than refining my ideas. But then people started subscribing. Even crazier, people started offering me money.

“If you can't explain it to a six year old, you don't understand it yourself.” ~ Richard Feynman

Writing, teaching, speaking, and communicating ideas is the last step in cementing in your understanding and mastery. They say “If you want to master something, teach it.” Write a book on something. Make a podcast, a blog. Teach a class on it. You will get better at your level of mastery.

Honorable Mentions

There are a few other neurocognitive tricks I have up my sleeve.

Incubation Period

The incubation period in cognitive neuroscience refers to a phase of problem-solving where the conscious mind temporarily disengages from actively working on a problem. During this time, unconscious cognitive processes continue to work on the task in the background, often leading to sudden insights or solutions upon returning to the problem. This phenomenon is thought to allow for the reorganization of information and the formation of new neural connections, potentially facilitating creative breakthroughs. The incubation period can vary in duration, from a few minutes to several days, and is often most effective when followed by a period of focused attention on the problem.

I first learned about this phenomenon when I read about studies testing decision-making with and without delays and distractions. It turns out that if you cram in a bunch of information, and then do something else entirely, your brain continues working on it in the background. Most people in STEM have stories where they wake up in the middle of the night with an answer ready-made, like it was just ejected from a toaster oven. I deliberately practiced this back in my IT job where I’d bash my head against the wall of a tough problem all week, ignore it all weekend, and solve it within minutes the following Monday morning.

Saturation Point

This one I learned from my wife, the librarian. When you’re digging through a pile of books, eventually you start reading the same things over and over again. With a large enough epistemic web, everyone is referencing everyone else. It’s sort of like the circular relationships you see in news articles online. Eventually, you run out of primary sources and new ideas.

This is the saturation point. There’s diminishing returns to reading any more on a subject, and instead it’s time to move on, talk about it, synthesize it, and put it into practice.

Subjectively, I feel this as boredom and frustration. The novelty signal wears off and it actually becomes difficult to focus on anything on the same subject.