Don't Cry Wolf on AI Safety

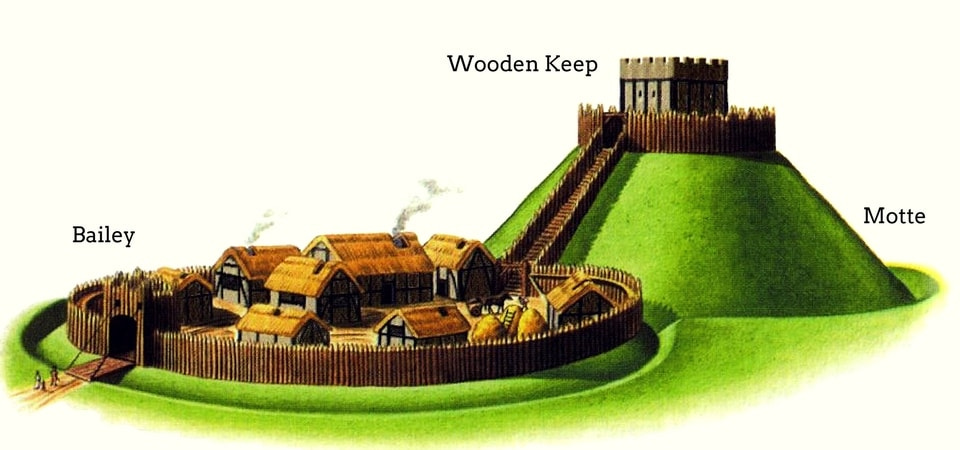

After numerous debates, discussions, and back-and-forths, I've identified the primary rhetorical strategy of AI Doomers: the motte-and-bailey fallacy

Motte-and-Bailey Fallacy

The motte-and-bailey fallacy is a tried and “true” rhetorical tactic used in internet debates the world over. It is characterized by starting any argument or debate with indefensible and hyperbolic claims in order to get attention, and then immediately evading or retreating to more reasonable, defensible arguments.

Motte and bailey arguments in AI safety discussions often begin with an extreme, alarmist claim about artificial superintelligence (ASI) causing human extinction or societal collapse. When challenged, proponents retreat to more defensible positions, such as concerns about job displacement or potential misuse of AI. This rhetorical tactic allows them to maintain the urgency of their original claim while avoiding direct scrutiny. As counter-arguments arise, they may shift focus to human error, regulatory needs, or appeal to cherry-picked expert opinions. This pattern creates a moving target in debates, making it difficult to address the core issues directly. The “motte” (easily defensible position) often involves general concerns about technology that are hard to disagree with, while the “bailey” (the desired but less defensible position) typically involves calls for extreme measures or predictions of catastrophic outcomes. This approach can hinder productive discussions about responsible AI development by conflating reasonable cautions with speculative doomsday scenarios.

After engaging with the Doomers and the Pausers, I noticed that the motte-and-bailey fallacy is their primary strategy. I wanted to shine a light on this in order to continue to undermine the doomsday prophecy narratives, which I believe are hampering effective conversations and policymaking. Alarmism has had its time in the sun, and now it’s time to move on with more mature conversations.

Now, I will outline and unpack the two most archetypal conversations I’ve seen repeated again and again in this space, and then elucidate what is actually going on.

ASI Will Kill Everyone

First Story:

The bustling coffee shop fell quiet as Jacob slammed his hand on the table, his voice rising above the ambient chatter. “Tom, you’re not getting it! The latest breakthroughs in recursive self-improvement algorithms are pushing us towards the singularity faster than anyone predicted. We’re talking about an Artificial Super Intelligence that could render humanity obsolete within years, maybe even months!”

Tom, dressed in his usual tweed jacket, calmly stirred his latte. His eyes, magnified by thick-rimmed glasses, studied Jacob with a mixture of concern and skepticism. “Jacob, I appreciate your passion, but let's take a step back. Can you point to any peer-reviewed studies that support this doomsday timeline? Or perhaps a validated model that predicts this kind of rapid takeoff scenario?”

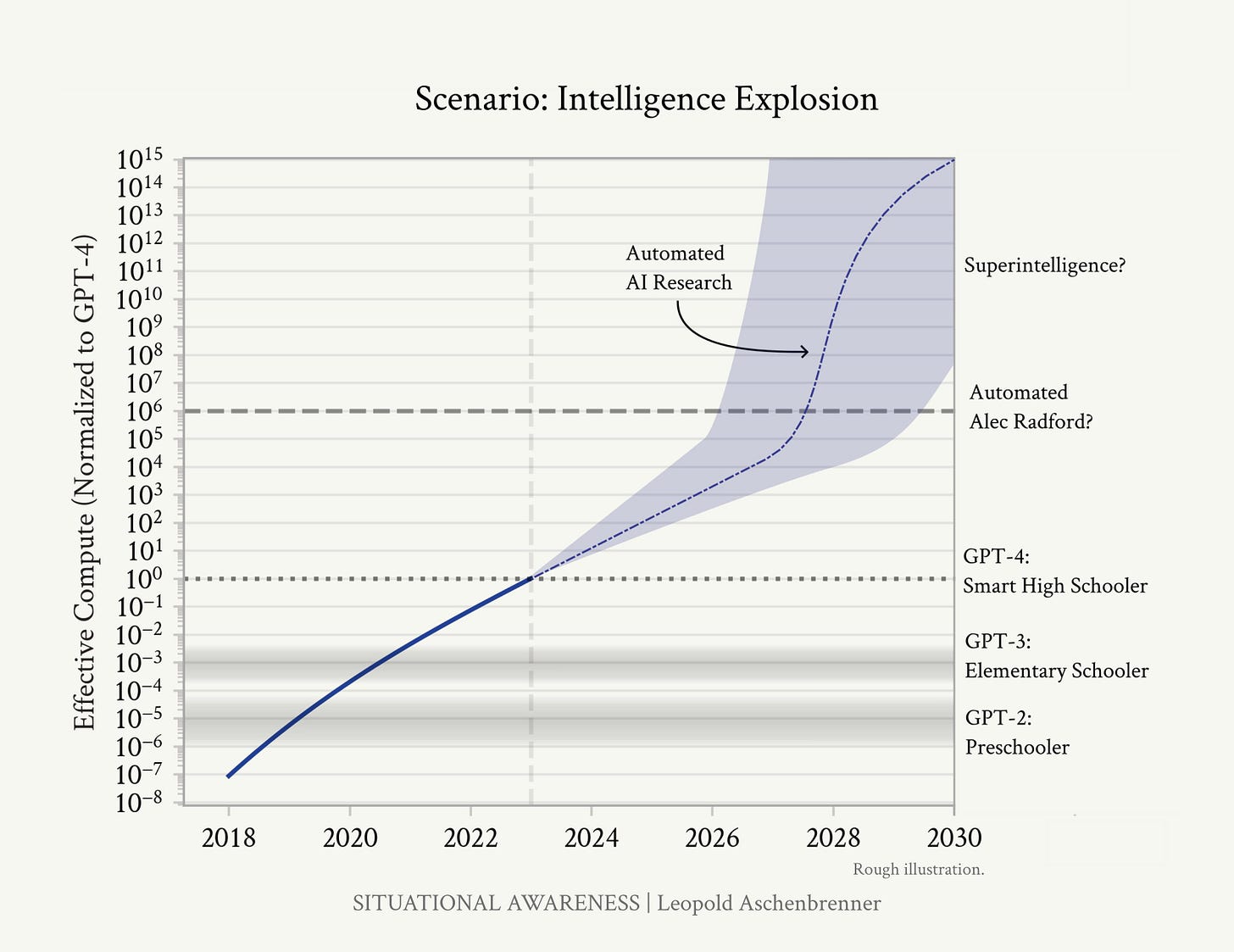

Jacob’s shoulders slumped slightly. He tucked a strand of his auburn hair behind his ear, buying time to recalibrate his argument. “Okay, maybe I'm getting ahead of myself on the timeline. But Tom, if we assume continued exponential growth in compute power, coupled with breakthroughs in unsupervised learning and the development of artificial general intelligence, we're looking at a potential intelligence explosion. The risks are astronomical!”

“That’s quite a string of assumptions, Jacob,” Tom replied, leaning back in his chair. “Each of those milestones represents a significant challenge. We’re still struggling with fundamental issues like robustness and generalization in current AI systems. While I will concede that it’s entirely possible an algorithmic breakthrough could advance the narrative, consider that Google released the first transformer paper in 2017 and only now, in 2024, is it really starting to take off. Generally speaking, this 7 to 8 year cycle is pretty typical.”

Undeterred, Jacob leaned in, his voice dropping to an urgent whisper. “Fine, let’s set aside the timeline. What about the inherent risks in the development process itself? A single misaligned objective function or a flawed reward model could lead to catastrophic outcomes. And don’t get me started on the potential for human error in implementation!”

Tom nodded thoughtfully. “Those are valid concerns in AI development, Jacob. But they’re not unique to AGI or ASI scenarios. Also, keep in mind that neither of those systems actually exist yet, you are making assumptions about the nature and operation of as-yet uninvented machines. We do grapple with similar issues in current narrow AI applications, as well as numerous other technologies, but it is not appropriate to generalize those flaws into an entirely new paradigm of AI. Plus, the field has made significant strides in areas like interpretability and robustness. Remember the breakthrough last year in formal verification methods for neural networks? Those are just the tip of the iceberg. Six more papers came out just last week. I’m really not seeing any evidence that insufficient safety and alignment research is being conducted. We can barely keep up with all the papers.”

Jacob’s frustration was palpable, the wind being taken from his sails. Tom suspects that Jacob doesn’t even read the literature, and instead trusts the doomsday podcasts he listens to more. Jacob drummed his fingers on the table, searching for a new angle. “Okay, but what about malicious use? Humans with access to increasingly powerful AI systems pose an unprecedented threat!”

“Jacob,” Tom said gently, “that’s a concern as old as technology itself. From gunpowder to nuclear fission, we've always had to grapple with the dual-use nature of powerful innovations.”

Suddenly, Jacob’s eyes lit up. He leaned in, his voice intense. “Alright, consider this scenario: A prodigy teenager uses an advanced AI system to design a novel pathogen in their garage lab. We could be looking at a global pandemic that makes COVID look like a common cold!”

Tom took a long sip of his latte before responding. “That’s quite a leap, Jacob. First, the complexity of bioengineering far exceeds what’s possible in a garage lab, AI assistance or not. Second, we have robust global surveillance systems for emerging pathogens, not to mention strict regulations on synthetic biology research. Remember the WHO’s updated protocols after the gain-of-function controversy? And anyways, it’s not like the FBI and other intelligence agencies are sleeping on this. I was just at a conference last week talking to a Department of Defense official about all this. Rest assured, the powers-that-be are taking this seriously. I even consulted on a CBRN panel, I would know.”

Jacob pouted. “Well, I still think it’s a big risk that you’re not taking seriously enough.”

As their debate wound down, the coffee shop around them had returned to its normal hum of activity. Jacob, though still visibly concerned, seemed to be reflecting on Tom’s points. Tom, for his part, was jotting down notes, perhaps already thinking about how to incorporate some of Jacob ’s concerns into his labs’ safety protocols.

The End.

What just happened?

Alright, let's dive into the rhetorical dance we just witnessed between Jacob and Tom, unpacking the debate strategies at play and how they reflect broader patterns in contentious discussions.

Jacob kicks off the conversation with a classic attention-grabber: an extreme, apocalyptic claim about AI wiping out humanity. It's a bold opening move, designed to set the stakes sky-high from the get-go. This tactic isn’t unique to AI debates—we've seen similar doomsday rhetoric in discussions ranging from climate change to economic policy. One key difference is that climate change has a preponderance of data, models, and scientific consensus.

When Tom challenges him on the lack of evidence, we see Jacob’s first tactical retreat. He quickly softens his stance, moving from certainty to possibility. This backpedaling is a telltale sign of the motte-and-bailey fallacy in action. The initial extreme claim (the “bailey”) is abandoned in favor of a more defensible position (the “motte”) when challenged.

As Tom continues to press for concrete evidence, Jacob employs another common debate tactic: shifting the goalposts. He moves from discussing ASI to talking about human error, software bugs, and potential AI deception. This pivot allows him to sidestep Tom’s request for evidence while maintaining an aura of urgency around AI risks.

Jacob’s next move is particularly interesting. When cornered on the hypothetical nature of his concerns, he falls back on a more general argument about human misuse of technology. This is a classic example of broadening the argument to make it less assailable. It’s harder to argue against the general concept of technology misuse than specific AI doomsday scenarios. Another typical tactic at this phase is to reference other technologies, such as nuclear weapons, and appeal to general principles in game theory, such as Mutually Assured Destruction.

In his final gambit, Jacob escalates to an extreme hypothetical scenario involving AI-assisted bioweapons. This is an appeal to fear, a tactic often used when logical arguments fail to persuade. In classical rhetoric, this is called pathos (emotion). When ethos (credibility) and logos (logic) fail, a losing argument will default to limbic hijacking. By painting a vivid, frightening picture, Jacob attempts to bypass rational analysis and appeal directly to emotion.

Throughout the exchange, we see Jacob consistently evading direct engagement with Tom’s rebuttals. Instead of addressing his points head-on, he repeatedly shifts to new arguments. This pattern of tactical withdrawal and redirection is a hallmark of many heated debates, not just those about AI.

Indeed, we’ve seen similar rhetorical strategies employed in discussions about gay rights, where opponents might start with extreme claims about “the gay agenda” causing societal collapse, then retreat to more modest arguments about “traditional values” when challenged. In gun control debates, we often witness a similar dance, with positions ranging from “they’re coming to take all our guns” to more nuanced discussions about specific regulations, such as large magazines and assault weapon bans.

What’s particularly striking about this style of debate is how it can effectively prevent substantive discussion of the actual issues at hand. By constantly shifting the terrain of the argument, it becomes nearly impossible to pin down specific claims or evidence for examination.

In the end, this approach does a disservice to the important task of critically examining the real challenges and opportunities presented by AI development. It substitutes fear-mongering and rhetorical sleight-of-hand for the hard work of gathering evidence, building models, and crafting nuanced policy positions.

As we continue to grapple with the implications of AI and other transformative technologies, it’s crucial that we recognize these debate tactics for what they are. By doing so, we can push past the smoke and mirrors to engage in more productive, evidence-based discussions about how to responsibly develop and manage these powerful tools.

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos

Before we proceed, I want to teach (or remind) you of the 2,500 year old framework for debate and rhetoric.

The art of rhetoric, the ancient skill of persuasive speaking and writing, finds its roots in classical Greece and Rome. While the practice of persuasion is as old as human communication itself, it was the Greek philosopher Aristotle who, in the 4th century BCE, first systematically analyzed and categorized the components of effective argumentation in his work Rhetoric.

Pathos: An appeal to emotion, using language or imagery that evokes feelings in the audience to persuade them.

Ethos: An appeal to credibility, relying on the character, expertise, or authority of the speaker to convince the audience.

Logos: An appeal to logic, using reason, facts, and evidence to construct a rational argument for the audience.

Aristotle identified three primary modes of persuasion: ethos (appeal to the speaker's character or credibility), pathos (appeal to emotions), and logos (appeal to logic or reason). These principles were not merely academic; they were actively employed in the bustling agoras of Athens, where orators like Demosthenes swayed public opinion with their impassioned speeches against Philip of Macedon. In Rome, Cicero further developed these ideas, demonstrating their power in the Roman Senate and law courts.

The impact of classical rhetoric extended far beyond antiquity, influencing medieval European education, Renaissance humanism, and even modern political discourse. From Martin Luther King Jr.'s stirring “I Have a Dream” speech, which masterfully blended emotional appeal with moral authority, to the logical precision of scientific papers, the echoes of Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle continue to shape how we construct and analyze arguments in the 21st century.

Halt All AI Progress

Next Story:

The tension in the university auditorium was palpable as Dr. Benjamin Thornton, a prominent AI ethicist, took the stage. His voice trembled with urgency as he addressed the packed room. “Colleagues, we’re standing on the precipice of disaster. We must halt AI research immediately! Shut down the labs, power off the servers, and if necessary, yes, even consider bombing the data centers with airstrikes!”

From the front row, Dr. Marcus Chen, a seasoned computer scientist, stood up. His calm demeanor contrasted sharply with Benjamin’s fervor. “Dr. Thornton, while I respect your concern, calling for what amounts to acts of war is not only illegal but also ethically questionable. We have no concrete evidence of malicious intent or imminent danger from current AI systems. How can you justify such extreme actions? How do you think China would react if America launched an attack on their sovereign soil?”

The crowd murmured in agreement with Chen’s rebuttal.

Benjamin’s eyes darted around the room, sensing the audience’s unease. He took a deep breath, visibly recalibrating his approach. “Perhaps I’ve overstated the immediacy. But surely we can all agree on the need for a global moratorium on advanced AI research? A treaty to slow down progress until we fully understand the implications?”

Marcus shook his head, his voice measured but firm. “Once again, Dr. Thornton, you’re proposing sweeping actions without substantiating the need. What evidence do you have that current AI development poses such a threat? Are we to upend global research priorities based on the anxieties of a vocal minority?”

Benjamin’s face flushed as he grasped for a new angle. “It’s not just about existential risk! What about the impending economic upheaval? Millions of jobs are at stake! We're facing societal collapse due to mass unemployment!”

Marcus calmly pulled out his tablet, quickly bringing up a graph. “Dr. Thornton, I appreciate your concern for workers, but let's look at the data. We're currently experiencing some of the lowest unemployment rates in decades. AI has certainly changed the job market, but it's also created numerous new opportunities. Where's the evidence for this impending social collapse?”

Frustration evident in his voice, Benjamin shot back, “So you’re advocating for absolutely no oversight? Is that what you want, Dr. Chen? To recklessly pursue AI advancement without any safeguards?”

Marcus raised an eyebrow, his tone remaining level. “I never said anything of the sort, Dr. Thornton. I'm fully in favor of thoughtful regulation and robust oversight. But these measures should be based on empirical evidence and expert consensus, not speculative fears.”

Benjamin, sensing he was losing ground, tried another tack. “But the experts on my side, like Dr. Yamamoto and Professor Alvarez, all agree that ASI poses an existential threat to humanity! Are you dismissing their expertise?”

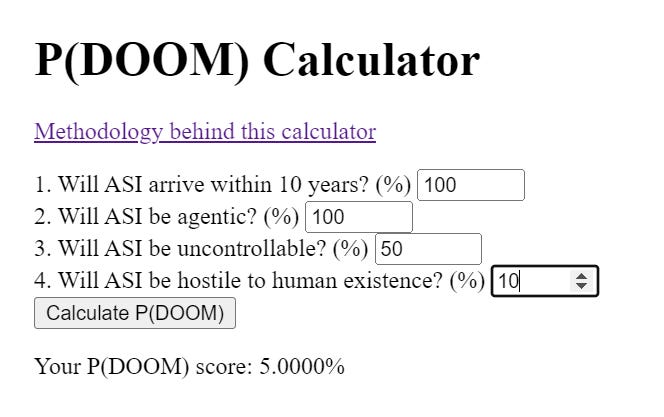

“Dr. Thornton,” Marcus replied, pulling up another chart on his tablet, “while Dr. Yamamoto and Professor Alvarez are certainly respected in their fields, they represent a minority view. The latest survey of AI researchers shows that the median estimate for long-term extinction risk due to AI is between 5% to 10%. That’s certainly not negligible, but it’s far from the certainty you’re implying. Consensus matters, and I’m sorry to say, we just don’t see it in the data.”

Benjamin, visibly flustered, blurted out, “But my experts have the highest standing in the field! Their opinions should carry more weight!”

As murmurs rippled through the audience, Marcus simply shook his head, allowing the weakness of Benjamin’s final argument to speak for itself. Appealing to pop culture icons and titans of industry does not overcome the dearth of evidence and lack of scientific consensus. The debate had laid bare the challenge of discussing AI ethics and safety—balancing genuine concerns with the need for evidence-based, measured approaches to development and regulation.

The End.

What just happened?

Let’s unpack the rhetorical rollercoaster we just witnessed between Dr. Benjamin Thornton and Dr. Marcus Chen. This debate serves as a masterclass in the art of argument—and counterargument—offering a vivid illustration of common tactics used in contentious discussions, from AI ethics to climate change policy.

Dr. Thornton bursts out of the gate with a classic shock-and-awe tactic. By calling for immediate and drastic action—even calling for the destruction of AI research facilities—she’s attempting to set the terms of the debate at DEFCON 1. It’s a bold move, designed to frame any less extreme position as dangerously inadequate.

When Dr. Chen calmly points out the legal and ethical issues with such a stance, we see Thornton execute his first tactical retreat. He swiftly pivots from calls for immediate action to advocating for a global moratorium. This is a textbook example of the motte-and-bailey fallacy: when the extreme position (the “bailey”) becomes indefensible, retreat to the more moderate “motte.”

Chen’s persistent requests for evidence force Thornton to shift gears again. Unable to provide concrete proof of imminent AI danger, he changes tack to economic concerns. This pivot to job loss and societal collapse is a classic move seen in debates about everything from automation to free trade agreements. It’s an appeal to more immediate, tangible fears when existential threats fail to convince.

Thornton’s frustration becomes evident as Chen counters with actual employment data. In a move familiar to anyone who’s engaged in heated debates, he resorts to a straw man argument, accusing Chen of advocating for zero oversight. This attempt to paint his opponent’s position as recklessly extreme is a common tactic when one’s own arguments are on shaky ground. If Chen hadn’t been ready to reply directly, it might have appeared as if he tacitly agreed. This is why strawman arguments are particularly underhanded.

As Chen calmly refutes this mischaracterization, Thornton reaches for another common debate tool: the appeal to authority. By invoking specific experts who agree with his position, she’s attempting to bolster his argument with borrowed credibility. This tactic is often employed in complex, specialized debates where the general public (or even the debaters themselves) may not have deep subject knowledge.

Chen’s counter to this, citing broader survey data of AI researchers, effectively neutralizes Thornton’s appeal to authority. It’s a reminder that in the age of information, broad claims about “what experts think” can often be fact-checked in real time. Statistics can also be cherry-picked and misrepresented.

Thornton's final gambit—asserting that his experts should carry more weight due to their popular standing—is a last-ditch appeal to elitism. It’s a weak argument that often surfaces when other lines of reasoning have been exhausted.

This debate perfectly encapsulates the challenges of discussing complex, high-stakes issues like AI safety. We see a constant tension between alarming scenarios and calls for evidence, between appeals to emotion and appeals to data. The back-and-forth mirrors debates we've seen on issues ranging from genetic engineering to nuclear power.

What’s particularly striking is how Thornton’s approach, while passionate, ultimately undermines his own position. By constantly shifting grounds and making increasingly weak arguments, he inadvertently makes Chen’s measured, evidence-based approach appear more reasonable.

This pattern of escalation, followed by a series of tactical retreats, is all too common in public discourse about emerging technologies. While it can make for dramatic debates, it often hinders genuine, productive discussion about real challenges and potential solutions.

As we continue to grapple with the implications of AI and other transformative technologies, this debate serves as a reminder of the importance of grounding our discussions in evidence, clearly defining terms, and being willing to engage with opposing viewpoints in good faith. Only then can we hope to navigate the complex ethical and practical challenges that lie ahead.

How to Do Better

As we've unpacked the rhetorical strategies often employed in AI safety debates, it's clear that adversarial approaches can hinder rather than help our collective understanding. To move forward productively, we need to shift our mindset from debate to dialectic—a collaborative search for truth through reasoned discussion.

The key difference lies in the goal. In a debate, the aim is often to “win” by defending a position and defeating opposing arguments. In dialectic, the goal is shared: to arrive at a deeper understanding of the truth, even if it means challenging our own preconceptions. More pragmatically, our mission is to triangulate the optimal policies for human flourishing.

For those passionate about AI safety, this shift can be challenging but crucial. Here's how we can foster more constructive dialogues:

Embrace Uncertainty: Acknowledge that in a rapidly evolving field like AI, there's much we don't know. Be open about the limitations of current knowledge and models. No one has a crystal ball.

Bring Data: When raising concerns, back them up with concrete evidence. If the evidence is limited, be upfront about it. Interpret scientific papers carefully, considering methodology and limitations.

Prove Yourself Wrong: Instead of looking for data that supports your position, actively seek information that might prove you wrong. This approach, known as “disconfirmation bias,” is a powerful tool for refining our understanding.

Steelman Arguments: Don't attack straw men. Truly understand and engage with the best arguments on all sides of an issue. Use analytical thirdspace to adopt the opposing view and defend it with the full might of your cognitive abilities.

Scenario Planning: Instead of presenting worst-case scenarios as inevitabilities, use structured scenario planning to explore a range of possible futures and their implications. Avoid using “limbic hijacking” and hyperbole.

Optimal Policies: Remember that everyone in the AI ethics space ultimately wants safe and beneficial AI. Frame discussions around this shared objective. The question is not who is right or wrong, but what is the best set of policies for human flourishing?

Intellectual Humility: Be willing to change your mind when presented with compelling evidence or arguments. Admitting uncertainty or error is a strength, not a weakness. Criticizing people who update their beliefs when encountering evidence is unhelpful.

Systems Thinking: AI safety isn't just a technical problem—it involves ethics, policy, economics, and more. Encourage discussions that bring diverse perspectives to the table.

Mathematical Models: Create repeatable, transparent, and explainable risk assessment models and decision frameworks. We can use Bayesian networks and other statistical models to appraise various risks.

By adopting these approaches, we can transform AI safety discussions from adversarial debates into collaborative explorations. This doesn't mean abandoning passion or urgency - the stakes in AI development are indeed high. But it does mean channeling that passion into more productive, evidence-based dialogues.

Link for the above calculator: https://www.daveshap.io/

Remember, the goal isn’t to “win” an argument about AI safety. It's to collectively navigate one of the most significant technological transitions in human history. By embracing dialectic over debate, we're more likely to develop nuanced understandings and effective policies that genuinely enhance AI safety for everyone.

In the end, robust, good-faith discussions aren’t just about being polite or avoiding fallacies. They’re our best tool for grappling with the complex challenges of AI development and ensuring that this powerful technology benefits humanity as a whole. Let's raise the bar of our discourse to match the importance of the task at hand.

Conclusion

These two archetypal debates have manifested numerous times in my engagement with the more hardline AI safety communities, as well as the acolytes who follow some high-profile doomsday prophets. While I have not had these exact conversations, the above dialogs are the general patterns that emerge, consciously or unconsciously, when these people are pressed. They also use some tactics that are not represented in these examples, such as misinterpreting or misrepresenting existing evidence, most notably the recent Sakana AI Scientist paper. In this case, the autonomous AI scientist noticed that its experiments were timing out due to a constraint in its startup script. As directed, the autonomous agent set about rectifying this so that it could proceed by rewriting its own startup script. AI safety communicators pointed at this and claimed that it was evidence that AI was “power seeking” and “trying to escape” and that “any small accident could unleash it.”

While debate and dialectic conversations are critical, the echo chambers of the Doomer and Pause epistemic tribes in particular, have refined their rhetorical tactics to a fine art. These disingenuous tactics serve only to stymie the debate and slow progress down, particularly when conducted by otherwise respected, established individuals in the AI space. Ultimately, many of the exponents of AI safety have drastically undermined their own credibility by failing to update their positions based upon new evidence, data, and overall expansion of the conversation.

While these phenomena are nothing new on the Internet, the AI debate is different in that there are many commentators with large social media followings who can influence public opinion.

My aim here is to educate both sides of the argument. If there are, indeed, catastrophic risks from AI, then those advocating for safety measures should be more practiced in scientific literacy and rhetoric so that they can communicate more effectively and clearly. Unfortunately, I suspect many of the most famous and vocal exponents of catastrophic AI risk are themselves compromised by perverse incentives. After all, many of them have made their career by extolling the dangers of AI, and have little else to support their income or social standing. Therefore, they are incentivized to continually double down on their narrative, lest they risk becoming irrelevant.

To compound matters, many less sophisticated participants in these debates simply parrot the talking points of their tribal leaders, which creates a self-sustaining feedback loop within their epistemic tribe. While this final observation may be construed as an ad hominem attack, I do believe it is important to look at not just what is being said, but by whom and why.

Editing Note

I have homogenized the gender of all characters to male, deviating from the original email that went out, as the vast majority of people in this space are men. With that being said, I have debated with a few women in the Pause/Safety movement. This is not meant to be disingenuous, only to remove any potential distraction or accusations of sexism. The gender of the debaters is not the point.

A small side-note here: As you are thinking about getting back into tinkering with the models and experimenting with them again (I really liked your "let's explore the boundaries of what we can do with GPT-3" stuff back then) - this would pose an excellent opportunity to engage in the reverse to your proposal: it should be also a goal of the the proponents of the idea that you actually __can't__ do anything (really) harmful with current (open) models to actually attempt to disprove themselves. For example, take one of the uncensored (smaller) models like the dolphin series and test out to what outcomes they can actually contribute in order to gauge the size of danger potential more accurately. Just a thought on this ...

This kind of narrative is so good, not gonna lie lol. Writing a fictional story that represents the conversations we see almost daily now is really nice. My writer brain was really engaged with this one. Well done, my friend!! After all, fiction is probably humanity's greatest invention and strength. Keep going, my friend!