Corporations are kinda evil, so how do we get rid of them?

Corporations exist for one reason: to coordinate labor and capital to provision goods and services more cheaply. What if we can find another way?

“Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like.” ~ Edward, First Baron Thurlow

Incentives and efficiencies are always the name of the game. Why is it easier to buy pens on Amazon than run to the store to do it? Your time is valuable, and instead of spending time getting in the car, going to the store, finding what you want, it’s just faster and more efficient for Amazon’s robots and warehouse pickers to grab them for you, throw them into a truck, and have one person do all the errands for your neighborhood. Functionally, that’s what an Amazon truck driver is doing. We’re offloading tedium to other workers.

The only problem with this arrangement is that Jeff Bezos has cornered the “last mile” market. You can buy everything on Amazon from hundreds of other stores, but few have last mile shipping down as good as Amazon. Furthermore, Amazon is basically the Walmart of the Internet—your “one stop shop for everything.” That means Jeff Bezos earns something like $30,000 per minute of existence because he’s skimming off the top of that efficiency gain. New markets usually work like this—first movers make boatloads of money because they figured out a new exploit or underserved methodology.

This is capitalism functioning as intended. Amazon would not exist without property rights and labor laws that allowed people like Bezos to accumulate wealth, steer the ship, and seek money. That’s the carrot. This is what I mean by efficiency and incentives. Bezos is incentivized to expand Amazon as much as possible because there’s always a reward, and he’s rewarded, fundamentally, for providing more efficient means of doing things.

That is the extent of my capitalism apologist streak.

Corporations are amoral, not immoral. Corporations, acting as conglomerate entities, have a few basic imperatives, not unlike amoebas or cancer: grow at all costs, dominate the environment. Basically, you become an apex predator or prey. In 1937, Ronald Coase identified why do firms even exist? In this case, “firm” means corporation, company, or other private organization. He figured out something pretty simple and straight forward—it is simply more efficient to organize capital and labor this way, which reduces transaction costs, thereby increasing efficiency.

That’s a fancy way of saying “it can be pretty expensive to set up a big operation, so rather than individuals selling goods and services directly to each other, sometimes you have to consolidate your efforts.” Think of it this way: it takes millions of man-hours to design and build a new Boeing airplane or Amazon distribution network. One person, even with all the property rights in the world, is never going to be able to do that on their own. A typical human, working 2,100 hours a year for 40 years is only going to produce about 84,000 hours of labor in their lifetime. But, what if you can divide and conquer? Labor specialization is the way to go, which means you can parallelize work. Many people can be working on many facets of the firm—from pouring concrete on a new warehouse to designing the next gen robot to driving the delivery truck.

This is why firms, or corporations exist.

Back in 1959, Edith Penrose wrote The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, in which she articulated what we all generally understand and accept today: corporations grow like cancer (not her words) and generally overextend themselves. The larger an organization gets, the harder it is to manage, and the less overall productive it becomes. When we say it becomes “less productive” we usually are measuring things like the “cost of doing business” goes up, and larger corporations produce fewer patents per employee. However, like pelagic megafauna, being bigger is often and advantage. No one messes with blue whales, orcas, or whale sharks just because they are so damn big. Likewise, competitive pressures often incentivize this ‘eat-or-be-eaten’ mentality in corporations, meaning they just keep growing as large as they can, as big as the market will allow them, lest they be undercut by another corporation or swallowed whole.

Now, let’s presuppose we want to destroy corporations. After all, this is what cyberpunk has been telling us since the 1980’s—global corporations are evil. They expand, exploit, and tip the scales in their own favor, growing like economic parasites, barely contained by consumer willpower and the government. Like cancer, they infiltrate government with corporate lobbyists, narrative distortion, and backroom deals. Revolving door politics between business and government have frozen out workers, and all that stuff. I’m sure I’m preaching to the choir.

Like Doctor Strange holding up the “one” finger to Tony Stark—there is one, and ONLY, one way that we can defeat corporations in the long run, and it’s a long shot. That is simple: find a more efficient (read: cheaper) way to provide goods and services than corporations.

Easier said than done.

Consider silicon chips. According to some wild off the cuff Grok DeepSearch research, it costs roughly $2B and 8 billion manhours of work to produce each next generation of chip.

Link here: https://x.com/i/grok/share/C8RgM8WBgiHw8J35L97smwNRh

Note: Perplexity estimates it’s much higher, reaching into the tens of billions potentially.

Right now, there are generally only two ways to organize that much capital and labor: executive fiat (i.e. governmental action, think NASA’s moonshot program) or private interests, namely for-profit firms.

Now, you could argue that the university system is a sort of decentralized approach to research, except that they never have to hit market efficiency. One of the biggest problems with academia is they don’t have to be tested against reality, not in a market at least. For university research, you only have to pass muster of “can this be reproduced in a lab” and even then, many labs exaggerate.

One advantage of the for-profit model is that it creates an avenue for psychotic visionaries to push the bounds, break things, and take big risks with other people’s money—namely VC firms like Sequoia. This, rather than taxpayer money, tends to work well enough. Capital markets exist around the world, speculating about the next big thing. This is how Ilya Sutskever got $1B in funding within months of leaving OpenAI. A bunch of wealthy investors are willing to bet on Ilya.

This market solution is pretty good, particularly when science and technology are ready. This is why there are many parallel efforts to crack quantum computing and nuclear fusion. It’s also why OpenAI has many competitors now. Yes, the glorious free market is doing its thing!

But what if there was another way to provision goods and services? Could you make an open source Amazon? A decentralized SpaceX? I know, this sounds like socialism or communism, and that’s not what I’m talking about. Think of it this way: we’re about to build AI systems that are infinitely smarter than Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg combined. But they are not people and don’t have property rights. So, who runs the ship? Do all of us get an opportunity to enact our vision with the help of super intelligent agents? The competition would be fierce, would a market even work, then?

When it takes companies like IBM, Microsoft, and Google many years plus billions of dollars to figure out quantum computing, it seems like a long shot that AI and robots alone could dislocate the corporate hegemony. After all, someone still has to own and operate the robots and AI! Furthermore, even if you have really good simulations, theory will only get you so far. Eventually you have to build a real thing.

Typically speaking, markets become saturated, competition rises, and the new kid isn’t special anymore. OpenAI has already been lapped by competitors, for instance. Amazon is still holding out because of their brick-and-mortar base of warehouses and truck fleets.

Schumpeter articulated all this in 1942 with his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy in which he described “creative destruction”—the generative process by which market competition erases old ways of doing things, and eventually consolidates new markets. Think about Ford. Everyone loves Henry Ford for revolutionizing automobiles. But guess what? Now it’s a global industry.

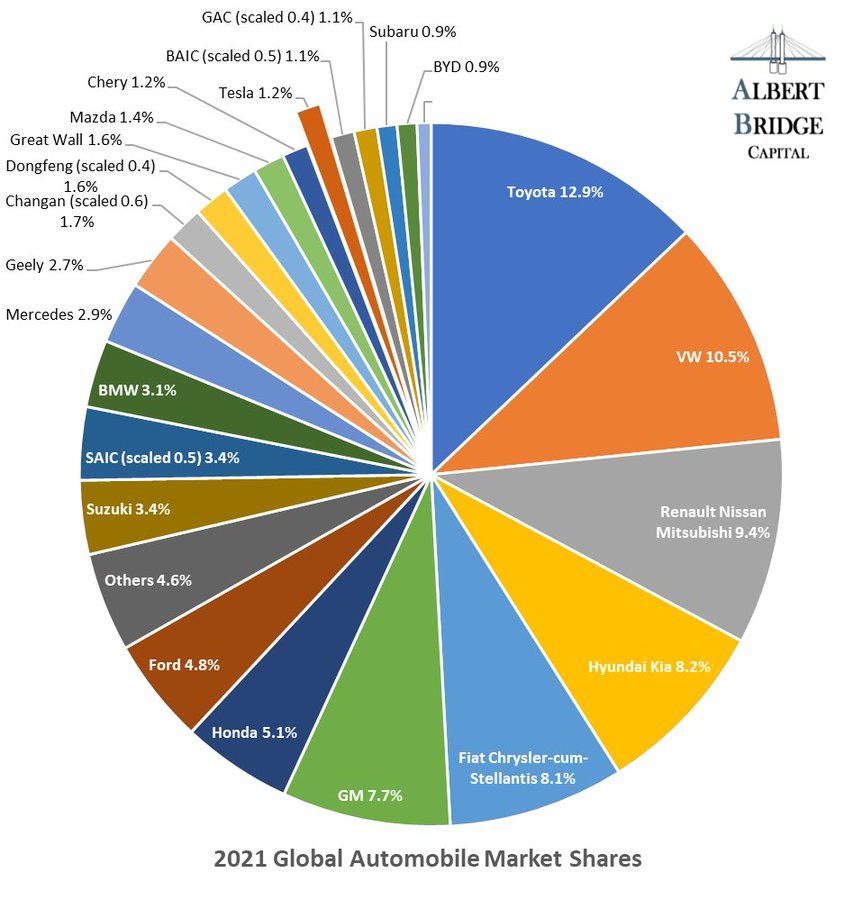

Is BMW evil? What about VW? Honda? All these companies have their rough spots and problematic periods. But overall, we’re generally glad they exist.

My point here is that maybe corporations are here to stay, mostly just due to the mammoth amount of capital and labor it takes to provision some goods and services. In some cases, I suspect that private interests will simply become untenable, profit margins will become too narrow, and some things, such as utilities, will become socialized or nationalized. Perhaps the combination of blockchain, AI, crypto, and robots will ultimately present new ways of doing things, but even if that’s the case, the market will probably still exist—where supply meets demand.

In the meantime, we might just need to learn to live with corporations and work to keep them in check through governmental transparency and accountability. Rather than destroy something that is a net-positive, maybe we need to focus on strengthening democratic institutions.

Just some thoughts.

People who are motivated mainly by money do not create Amazons or Teslas.

Corporations exist to facilitate some initial person or group's vision, to express their values, and to achieve some goals that they value.

They make money when other people also believe that what they produced is in fact valuable to those people who are buying the product or service.

But beyond that, corporations are subject to evolutionary processes... Capitalism is evolution applied to human organizations.

Evolution, because it optimizes for many important variables at a time... Produces systems that are rarely all that clean and pretty when you start looking at them deeply.

It's like democracy. Corrupt governments are a natural byproduct of the fact that rule requires compromise between major groups who have different values and interests.

So that, from the perspective of any of those groups (who don't respect the others), the compromises appear corrupt.

The problem is in some ways less with the system, and more with human intelligence being too shallow to properly grasp the complexity of what works in the real world.

That and most of us were raised to garbage fables as kids, that just plain did not encode useful frameworks of real world understanding w.r.t what does and doesn't really produce better outcomes.

It's hard to really fix wrong understanding that is part of the foundational framework with which you understand the world.

We may be pleasantly surprised by what is possible with future technologies, ASI being a prime example. What if the energy problem is solved, and energy becomes unlimited and essentially free? New manufacturing techniques that we can only imagine today might erase the competitive advantages of big corporations. It feels like we just have to limp through the transition period without killing each other in enormous numbers (our own stupidity being a way bigger risk than a terminator AI in my opinion).